“It’s funny,” says Sully screenwriter Todd Komarnicki, “From the outside looking in everyone joked on the Internet, ‘How can you make a movie about something that lasted seven minutes?’”

Todd Komarnicki

When it was announced that a movie was being developed about the emergency water landing of US Airways Flight 1549 on the Hudson River on January 15, 2009, screenwriter Todd Komarnicki was aware of the expectations. The entire event – from the plane’s takeoff at New York’s LaGuardia Airport to the successful rescue of all passengers and crew members aboard – took place in about thirty of the most unbelievable New York minutes.

What Komarnicki knew is that much of the story of Flight 1549 occurred afterwards, as pilot Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger, First Officer Jeff Skiles, and the rest of the crew were grilled by questioning from the National Transportation Safety Board for months to determine whether Sully – who became a national hero overnight – made the right decision to land his plane on the river or if he took an unnecessary risk.

The comprehensive investigation also led Sullenberger – a pilot who had devoted his life to airline safety even before the incident that launched him into national fame – to question his actions until, ultimately, he was vindicated and later honored for his heroism.

Komarnicki’s screenplay – directed by Oscar-winning director Clint Eastwood – is based on Sullenberger’s 2009 memoir Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters.

Prior to Sully, Komarnicki wrote several novels and had two screenplays produced as films – 2003’s Resistance (which he directed himself), and 2007’s Perfect Stranger. During the same period, he also produced numerous projects – most notably, the 2003 Christmas classic Elf. Being based in New York, Komarnicki felt a personal connection with the story of the seemingly miraculous landing on the Hudson River.

Creative Screenwriting spoke to Komarnicki about how he successfully pitched for the Sully job, his storytelling theory of “the eternal now,” what he learned from working with Eastwood, and the screenplays for two of his upcoming films, The Professor and the Madman and The God Four.

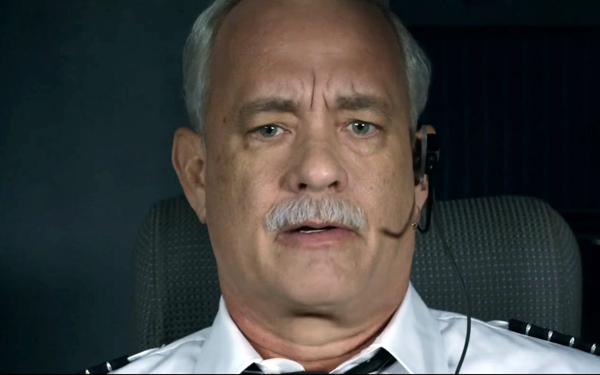

Tom Hanks as Chesley ‘Sully’ Sullenberger and Aaron Eckhart as Jeff Skiles in Sully © 2015 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved.

How did you get involved with this project?

The producers, Frank Marshall and Allyn Stewart, had optioned the book that Sully had written. A friend of mine who I produced Elf with, Jon Berg, is an executive at Warner Bros. and he sent me a clipping about the book being optioned. He wrote a little note that said, “You should write this movie.”

I reached out to Jon and said, “This is fantastic! Is this a Warner Bros. movie?,” thinking I had a leg up since I knew Jon so well. He said no, but ironically it would turn out to be a Warner Bros. movie years later when Clint Eastwood got on board.

I just went out for the job. I happened to be the first of many, many people who pitched for the job. After they talked to the town they came back and said, “Well, what we heard first we liked best.”

The event that the film focuses on happened in about half an hour. What went into your writing process in deciding what the rest of the film would be about?

When you’re sitting with Sully’s book and you’re sitting with Sully himself, there is an abundance of story. There was even more that we could have done. Clint made a really streamlined movie, which is fantastic and serves the purposes well at the perfect length. But there was lots of material to work with.

When you’re sitting with Sully’s book and you’re sitting with Sully himself, there is an abundance of story. There was even more that we could have done. Clint made a really streamlined movie, which is fantastic and serves the purposes well at the perfect length. But there was lots of material to work with.

It wasn’t really a challenge of what to do with the event since that is the thing everyone knows about, it was more about how you parse out the information about the man slowly falling apart and becoming a hero in the eyes of the world when internally and with the investigators it was actually seemingly going the other way.

A common approach in biopics is to tie a subject’s entire life to one dark secret in his or her past and fill the movie with flashbacks. In Sully, you used flashbacks very sparingly. Why is that?

The first thing I would jump out against is the word “flashback.” That is how it’s typically understood, and I don’t like flashbacks. What I did in Sully – and I try to do in anything that deals with the past impacting the present – involves a storytelling theory that I call “the eternal now.”

We carry with us everything that has happened, and not in an esoteric kind of way. We have it in us, and we are shaped by what has gone before. We have a handful of memories that we can easily access, but for the most part we forget the majority of our days. Then there is what is happening right now, and how this moment impacts our future. So it’s always eternally now.

Using that as a rule in storytelling, especially a subjective story around one particular hero and his journey, it allows for a camera to lean in a little closer, go into the actor’s eye, or drift past his shoulder and take you anywhere because you’re entering his bloodstream and memory.

As long as you come back to where you started that, then it’s not a flashback. It’s literally what the character is living through and allows the audience to join in on what could be very distancing, but works in reverse and makes us feel more in touch with Sully. It becomes more intimate.

Often, flashbacks are just flashbacks. They’re lazy storytelling, and they’re there to overtly tell the audience what to feel. That’s the opposite of what I’m trying to do. If I wind up with a script with what I consider a flashback, it definitely gets taken out.

Tom Hanks as Chesley ‘Sully’ Sullenberger in Sully © 2015 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved.

The National Transportation Safety Board representatives are the antagonists in the film. Not only is this an external conflict, but their browbeating leads to Sully’s internal conflict. Can you talk about developing conflict on both levels?

The other challenge is the fact that the investigation took place over nine months, and I had to collapse it into four days! [Laughs]

I would say the antagonist here is definitely Sully himself because of the PTSD and because he’s a guy who lives his life via control. That made him a great pilot and made him capable of landing that plane on that day. But when control is wrested from him – there’s the scene on Fifth Avenue where he’s jogging with Skiles and he says, “I want my control back, I want my life back” – that shakes him to his core.

When you get shaken that way, you start to have self doubt across the board. We all have that dark night of the soul when we tell ourselves that we’re terrible parents, terrible writers, or terrible human beings. We have to push off against that and get back on our feet, but when there are other people who are telling you that you may have made a mistake it can pile on and convince you.

I would say that the other side of the antagonism is not the investigators, it’s the investigation. The simple fact is for nine months this guy did not know if he would ever fly again, if he would have a pension, and if he would be sued by everyone on board, by the airline, and by Airbus. That Sword of Damocles over anybody’s head – and certainly over the head of a man who lived his whole life around safety and who fought for airlines to be safer – is painful irony.

He was sitting on this edge, and one little nudge could’ve pushed him over.

The film touches on the negative stories in the news around the time of the Hudson landing. Why was it important to provide that context?

As a New Yorker I feel very, very close to how differently it felt when we heard this piece of news as compared to everything else that was circulating. Certainly, news with an airplane in it had never been good. We were in bad shape. The whole economy was about to fall apart, and New York was the centerpiece of it. All the bad financial news was coming out of New York.

It was just a sorrowful time. It was also the dead of winter, and it’s not a place where you actually see something bloom. This story was just a giant bouquet of flowers for the city and the world because good news just doesn’t get reported. It’s perpetually bad news, and I think that’s why this is resonating. Life is made up of more good news than bad news – that’s how we move forward, raise families, and go to school – we do that based on the fact that there’s more good news than bad news.

But if you look at our culture and watch what is sold to us every day, we’re told it’s only bad news. This movie puts the lie to that.

Tom Hanks as Chesley ‘Sully’ Sullenberger, Shane P. Allen as a rescued passenger, and Aaron Eckhart as Jeff Skiles in Sully © 2015 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Speaking of how it happened in the dead of winter, Sully ends with one of the best one-liners in recent memory. Did you come up with that?

I wish that were my doing! Jeff Skiles is a very funny guy and that’s how the actual NTSB hearing wraps up. That’s the last line of the transcripts. That informed me to allow him to be funny throughout the movie, which was really liberating. But that line is his.

As the screenwriter, what did it feel like when you learned that a Hollywood icon like Clint Eastwood would be directing the film?

Well, I got a little star struck. My wife and I did a dance in the kitchen with a lot of singing and praising God. It was quite an amazing moment! I’m an enormous fan of Clint Eastwood’s. Unforgiven is one of my favorite films of all time.

He’s directed so many iconic moments. Think about Mystic River with the crane shot pulling out when Sean Penn is screaming, “Is that my daughter in there?” He’s left an indelible mark on cinema and our cultural memory bank. To know that he was going to be pointing the camera and saying “Action” and “Cut” gave me total confidence that we’d wind up with something special.

Clint Eastwood and Tom Hanks on set of Sully © 2015 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved.

You wrote the original screenplay for The Professor and the Madman, about the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary. The concept sounds fascinating, especially to writers. Can you talk about writing the screenplay for such a unique story?

Presently it’s being rewritten by the director of that movie, so I don’t know how it’s going to be different from what I scripted until the movie is done. But in terms of writing that script and working on it for a few years, it was beautiful. It’s about words and language, and that’s your toolbox for a writer.

The two men, Dr. Murray and Dr. Minor, pulled off a miracle, which is the miracle of the English language, in giving us a dictionary that has become definitive over the years against impossible odds. But both of them were treated with utter disdain.

In fact, Dr. Murray, who was the driver behind the whole project, was only chosen because the dons at Oxford had failed two previous times to pull off a dictionary. They actually knew they were going to fail, so they hired this Scottish guy who was less than credentialed so when it failed a third time it would fall on him. Beautifully, he dons that cape and superheroes his way into the history books.

To be able to write about the beauty, power, and necessity of language was a complete honor.

You also will be returning to directing with The God Four, which you also wrote. Can you talk about directing your own screenplays as opposed to working with a director like Clint Eastwood?

Clint shoots the script, so it’s as if I had the chance to protect my writing, which is an awfully nice feeling. There was no vulnerability with working with Clint because once he likes something that’s what he wants to make.

One of the many things I learned watching Clint direct is how a set should be. It should be quiet as a library and have people pulling in the same direction without stress. There’s a lot of artificial agita that occurs on movie sets, usually driven by insecurity, ego, and people needing to be seen.

It’s one of the things that sets Sully apart. At the end of the movie, he says, “You can do anything if you’re never in a hurry.” That’s actually a quote from my dad who said that to me my entire life. He was completely right.

That’s what Sully’s life is about, and it’s how he pulled off that miraculous landing.

That’s how I’m going to direct when I go back to set in the spring.

Featured image: Tom Hanks as Chesley ‘Sully’ Sullenberger in Sully © 2015 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved.

[addtoany]

Before You Go