“There was nothing else I ever wanted to do,” screenwriter and playwright Kate Gersten recalls. Growing up in New York City’s vibrant theater scene, Gersten was immersed in creativity from the start. Her father worked as a stage manager, her mother was a dancer, and her uncle produced shows at Lincoln Center Theater.

“I started writing when I was a little kid and my sister was my half sister. She’s twenty years older than me, so I kind of grew up spending a lot of time by myself.” With both parents working late – her mother wouldn’t return until 8:30 each night – Gersten developed a rich inner life. “I think that helped me develop my imagination from a young age,” she recalls.

The family’s regular attendance at Broadway shows shaped her artistic sensibilities and career aspirations. “It didn’t seem impossible because my family was creative. I just grew up around it – knowing that world. My first play that I wrote that was produced was a comedy. It was like a wild sci-fi comedy,” she continues.

Her work evolved to include more serious undertones during her time at Juilliard’s prestigious playwriting program. It was there that she wrote The Last Showgirl, originally as a play, marking a significant shift toward drama.

Kate Gersten. Photo by Zoey Grossman

However, her career initially took off in television comedy. “I was hired on Mozart in the Jungle and then The Good Place and then Schmigadoon!. And so, I was really making my way in the television landscape as a comedy writer, or maybe like the more emotional one of the comedy writers,” she explains.

Birth of The Last Showgirl

The inspiration for The Last Showgirl came from an unexpected source – Gersten’s first writing job crafting material for a Las Vegas show. While there, she witnessed a performance of Jubilee, the last major showgirl spectacular in Vegas.

“There were 85 women on the stage, 45 people on the crew,” she recalls. “That was minimized from the way that it was in the 80s and 90s. It was a 40-year-old show.” The nearly empty theater that night left an indelible impression.

“There were only 15 people in the audience when I went to see it. Mostly these stoic international businessmen who were barely even clapping. But the ethos of being a showgirl was so alive with these women.” The experience resonated deeply with Gersten’s own understanding of performing arts.

“The lives of dancers are so fascinating to me because there’s not a lot of glory to being a dancer. You’re never gonna be rich. You’re never gonna be famous. It’s really all about dancing in the moment and how it makes you feel.” The impact was immediate. “I went back to New York. I wrote the play in a week. We were workshopping it at the roundabout a month later.”

Finding Their Shelley In Pamela Anderson

The path to screen wasn’t straightforward. The original 125-page play had been optioned for both Broadway and London’s West End, but finding the right actress proved challenging. The breakthrough came during COVID lockdown, when Gersten’s cousin-in-law, Gia Coppola, read the play and suggested a film adaptation.

It was Gersten’s husband who first made the connection after watching Pamela Anderson’s Netflix documentary. “Finding a woman who is experienced as an actor who doesn’t have a regality to her is very tough,” Gersten explains. “Somebody who can carry this movie and who has stayed soft is just really like finding a unicorn.”

Anderson’s connection to the material was immediate. “She really has this artistic instinct that nobody has acknowledged,” Gersten notes. “Gia saw that in her right away when she watched the documentary. She said, ‘I’m recognizing that here is a person who is unsung, who’s been misrepresented, who’s been misunderstood.'”

The film became a true family collaboration, with Gia directing and Gersten’s brother-in-law Robert Schwartzman producing. From the start, Gersten knew she wanted more involvement than writers typically get.

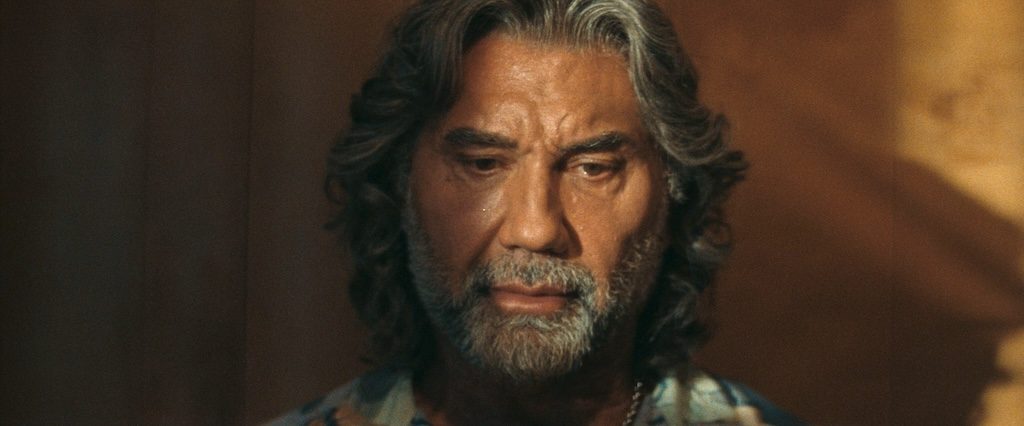

Eddie (Dave Bautista) Photo courtesy of Roadside Attractions

“When Gia asked if she could direct it, I said, ‘Yes, but I really wanna do it together. I don’t want to just be a writer who gets told, okay, thanks for your pages, bye,'” she recalls with a laugh. “I want to be the only writer that ever touches the script. Even with ADR.”

The tight schedule – just 18 days of filming on actual film – made her presence on set invaluable. “We just didn’t have the budget to do any more than that,” Gersten explains. “I could be there to remind everyone, ‘This is the scene before this happens. This is the scene after.’ Just keeping all those checks and balances really tight.”

Advice To Screenwriters – Finding Your Medium

Today, Gersten approaches different projects based on their natural fit. “I’m writing something right now about two moms who are best friends,” she says. “Even just in that little tiny bit of information, it’s a TV show. It’s ongoing. It’s not a play. But I’m also writing something about a family reuniting after years apart at Thanksgiving. And that is a play.”

For aspiring writers hoping to work across multiple formats, Gersten emphasizes the importance of daily practice. “I’ve been writing every day for so many years, since before I was a professional writer,” she shares. “Just always know your writing is just for you. That’s the way that I felt. I was like, my writing is for me.”

She references a valuable concept learned from writer Tanya Barfield called “composting” – the idea that even seemingly unusable writing creates fertile ground for future work. “Composting is when you write, it creates this great rich soil of what you can draw from in the future, whether it’s characters or scenarios or conflicts,” she explains. “It all will come back around, and it doesn’t all need to be usable at the time that you’re writing it.”

This philosophy has served her well across theater, television, and now film. When asked about the adaptation process of The Last Showgirl from stage to screen, Gersten lights up. “The play has a lot more focus on the arcs of every single character,” she says. “In adapting it to a feature, we really were narrowing the focus down onto Shelley. It was a great experiment. I always say it’s better to cut than to have to add.”

This interview has been condensed. Listen to the full audio version here.