- Writing Exposition To Make Your Script Pop (Part 1)

- Writing Exposition To Make Your Script Pop (Part 2)

Exposition is the beating heart of any story be it script, novel, song, article or poem. Building to a solid ending requires layering and delivering information in specific ways to make that ending work.

But exposition isn’t just telling the audience something. It involves many aspects of a script – or any story for that matter. There are techniques to use and understand.

Exposition can do severalfold things. It reveals character, furthers plot, sells the theme, creates the emotional core – just about anything you can imagine.

Let’s examine some techniques that can make the magic happen.

1) Straight Exposition

The most common way to do exposition is to just say it. The characters tell the audience what’s needed for them to know. Having taught for years, written and sold scripts for even longer (and written a few books) I’ve seen that the most common errors people make is this: They tell too much or force the exposition on to the audience. It requires some practice to get this balance right. The more you write, the better you will get at it.

There are two basic forms of straight exposition: dialogue and narrative (action). Forced exposition (mentioned above and which we’ll cover later) is when a character tells another character something that they already know and it’s done just to inform the audience.

Something like:

BRAD

You know that I can’t help it. I have <insert disease here>.

SANDRA

I’m your sister. Of course, I know that.

In the larger scheme of things this isn’t that horrible. It’s just a few lines and it could pass muster if necessary. But a better way to do it would be something like this:

BRAD

You know I can’t help it.

SANDRA

You always use <disease> as an excuse.

You’ve been doing it since we were kids.

So, which one’s better? Glad you asked.

2) Subtext

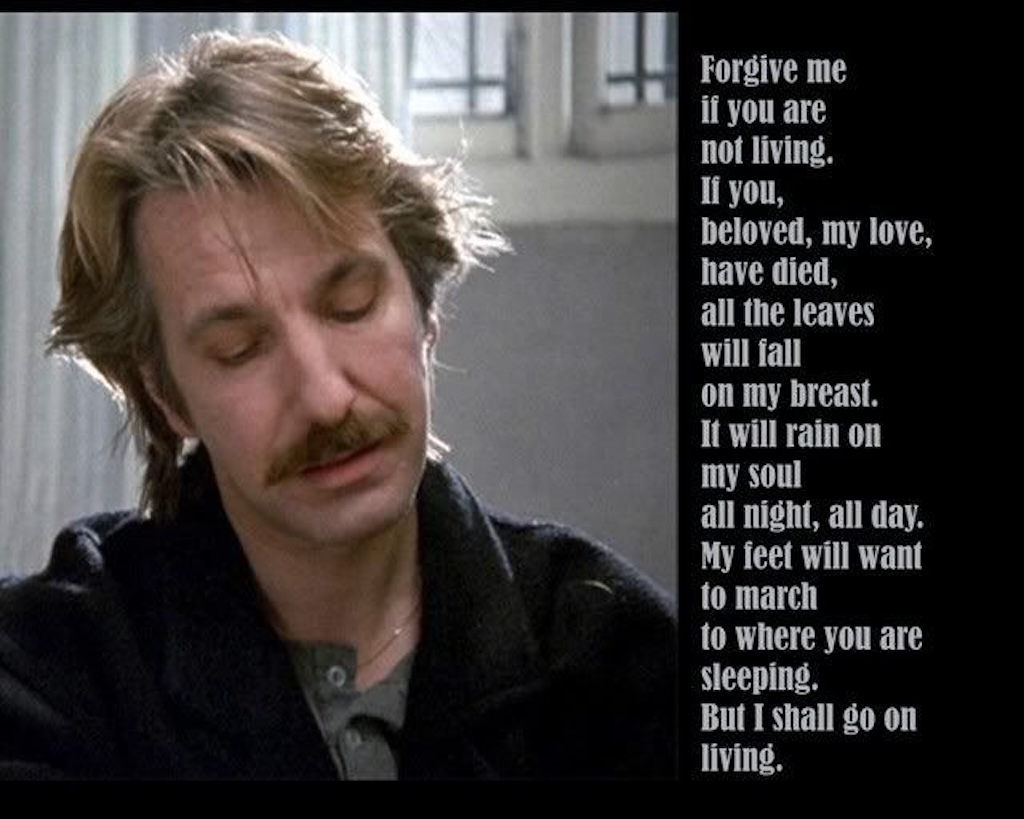

In the brilliant Truly, Madly, Deeply called the thinking person’s Ghost and written by Anthony Minghella (gone far too soon) Jamie (Alan Rickman), a ghost, is trying to say goodbye to his former lover, Nina (Juliet Stevenson). Different worlds and directions is the point of this tale and both have to come to accept that.

As ‘truly, madly, deeply’ in love as they are, they can no longer be together.

Jamie (Alan Rickman) in Truly Madly Deeply. Photo courtesy of BBC Films

Sitting on the floor, both are not sure which way to go with their relationship, Rickman’s character recites a Pablo Neruda poem. He asks her how her Spanish is, he says the poem, and she then translates each line. Not only does this technique give us the information, it does so in a compelling and suspenseful way.

What is the point, we’re asking? What is Rickman’s character trying to say?

RICKMAN

Perdoname.

JULIET

Forgive me.

RICKMAN

Si tu no vives.

JULIET

I know this poem. If you are not living.

RICKMAN

Si tu, querida, amor mio, si tu te has muerto.

JULIET

If you, beloved, my love, if you have died.

RICKMAN

Todas las hojas caeran en mi pecho.

JULIET

All the leaves will fall on my breast.

RICKMAN

Llovera sobre mi alma noche y dia.

JULIET

It will rain on my soul all night, all day.

RICKMAN

Mis pies querran marchar hacia donde tu duermes.

JULIET

My feet will want to march to where you are sleeping.

(beat)

Your accent’s terrible.

RICKMAN

Pero seguire vivo.

JULIET

My feet will want to march to where you are sleeping,

but I shall go on living.

At this point, Juliet crosses the room to him, unwilling to accept what he’s saying which is,”We can’t do this.” Quite emotional as she struggles to accept what she couldn’t at the beginning of the film.

Wow. Just incredible (and crucial!) dialogue exposition, but done in such a brilliant way.

3) Monologuing

Most of us can’t get away with this, but the amazing Aaron Sorkin is fearless (and talented).

To introduce his character Will McEvoy in The Newsroom played by Jeff Daniels who is on a panel at a college he pushes the character into this speech.

When asked what makes America the greatest country in the world, Jeff Daniels’ character out of frustration with the clichés spouted by the other panelists finally answers the question

WILL MCAVOY

And, yeah, you, sorority girl. Just in case you accidentally wander into a voting booth one day, there are some things you should know, and one of them is there is absolutely no evidence to support the statement that we’re the greatest country in the world. We’re seventh in literacy, 27th in math, 22nd in science, 49th in life expectancy, 178th in infant mortality, third in median household income, number four in labor force, and number four in exports. We lead the world in only three categories: Number of incarcerated citizens per capita, number of adults who believe angels are real, and defense spending where we spend more than the next 26 countries combined, 25 of whom are allies. Now, none of this is the fault of a 20-year- old college student, but you nonetheless are without a doubt a member of the worst period generation period ever period. So when you ask what makes us the greatest country in the world, I don’t know what the f*** you’re talking about. Yosemite?

Jeff Daniels (Will McAvoy) Photo courtesy of HBO

This goes on another few minutes. Almost four minutes of straight monologuing and it’s brilliant. What really sells this, despite that we don’t know anything about Jeff Daniels’ character, is his leaning into the screed – and MacKenzie McHale, the Emily Mortimer character who is holding up signs in the audience (or actually isn’t). It’s just Will McAvoy (brilliantly) imagining his ex-wife, the voice of his conscience. A really interesting way of revealing his inner thoughts and something that’s definitely been on his mind.

4) Visual Exposition

Showing is the strongest part of any screenplay. Because we work in a visual medium, we scriptwriters are blessed to be able to tell our stories, at least in part, with powerful images.

An oldie but goodie is an iconic moment from the Cameron Crowe movie Say Anything where Lloyd Dobler (John Cusack) stands outside Diane Court’s (Ione Skye) window, holding a boom box playing Peter Gabriel’s In Your Eyes. Yes, the song conveys a lot (another form of exposition, music) but the iconic image of him doing this, even after it starts to rain, tell a crucial part of the romantic comedy.

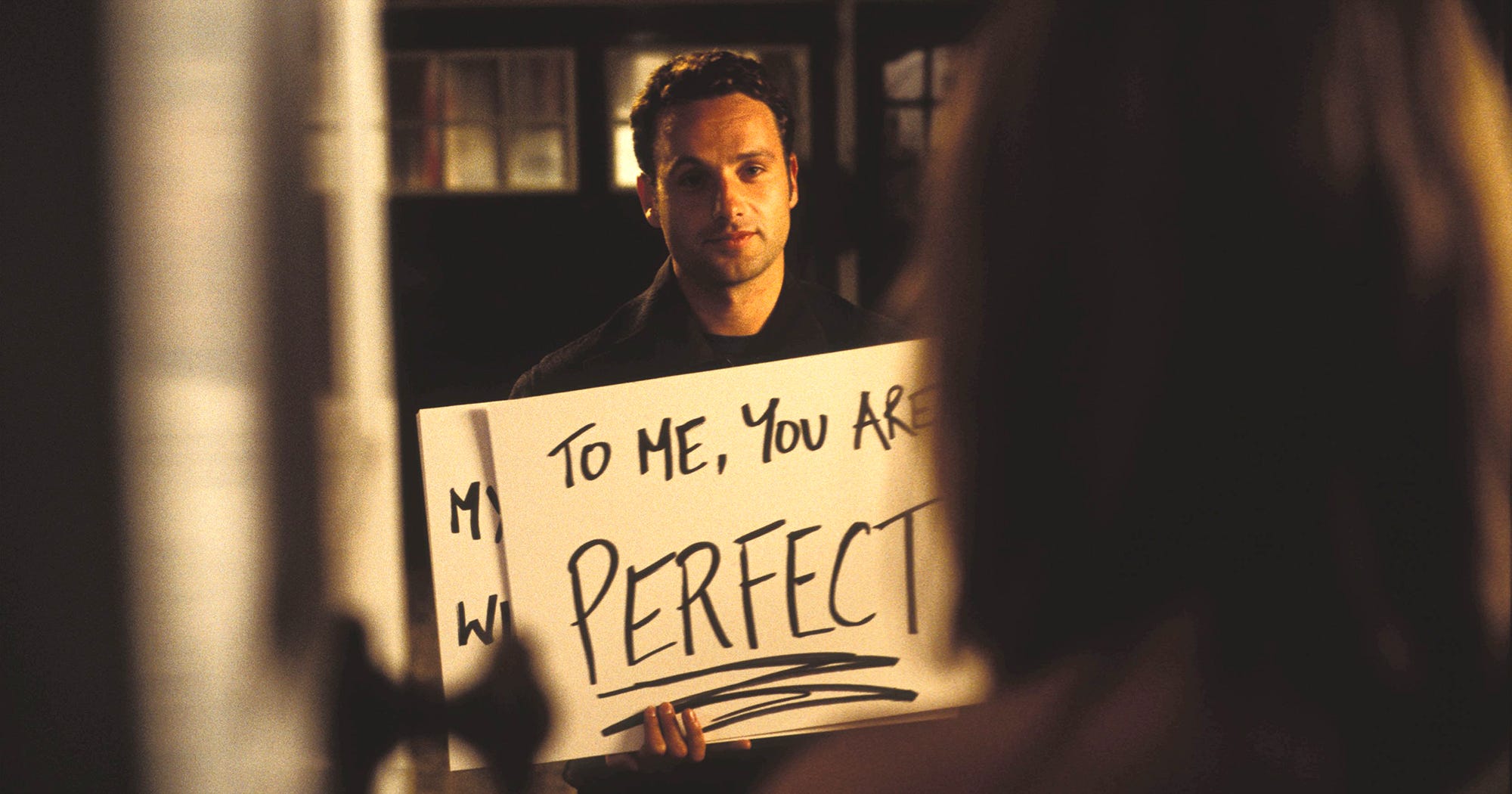

To stay in that genre a bit, the movie Love Actually has Mark (Andrew Lincoln) at Juliet’s (Keira Knightley) door, and instead of saying a word, he pulls out a set of cue cards and rolls them one by one to profess his love for her. This moment has been satirized in comedy routines including SNL by Pete Davidson and Amy Adams. Lincoln himself reprised the moment to promote Red Nose Actually (the movie reunion) on the BBC.

I’ve also seen this done a lot lately: The doctor (or cop) delivers bad news from a distance, away from the camera and audio. All we see is a somber character who is being told something, and then a shattered one as they are informed that so and so didn’t make it.

Writing those scenes with dialogue is always challenging and it’s easy enough to allow the actors to deliver the moment visually. It also has more impact because without sound so you’re wholly focused on the moment, not distracted by the audio.

It’s solid film/TV technique and that great storyteller Alfred Hitchcock said it best when he stated that you should still be able to tell what’s going on in any movie even if you turn off the sound.

In My All American the main character, the real life Freddie Steinmark played by Finn Wittrock, suffers an unimaginable medical experience. Nothing speaks louder or clearer to this character’s strength and resolve than him hobbling down a hospital corridor on crutches determined to get to the Cotton Bowl.

5) Exposition Through Isolation

In Dear White People the radio/podcast at the college is manned by one the main characters. Like in the movie and series M.A.S.H. where expositional announcements were piped in through the loudspeaker system, information is monologued by the Samantha White character (Logan Browning in the series, Tessa Thompson in the film) that varies from the political to the personal. It’s insight into the character and the situation that has no specific impetus at times but never feels inappropriate or out of context.

This is a type of oracle or Greek chorus and it’s incredibly effective.

In Five Easy Pieces, Robert Eroica Dupea (Jack Nicholson) talks to his stroke-stricken father – it’s actually heartfelt confession. The father is unable to respond but we still get a tremendous insight into Nicholson’s character. It’s quite a powerful and emotional scene which enlightens us to his previous (and future) behavior.

In Woody Allen’s Mighty Aphrodite he has an actual Greek chorus to give us information and set up scenes.

Epistolaries, scripts written with a character writing letters or a diary, also serve as good exposition techniques. Frankenstein, the book that launched hundreds of films and the horror movie genre, is told in epistolary fashion.

A modern-day equivalent would be a blog or podcast.

6) Montages & Voiceovers

Montages and V.O.s are also techniques to reveal information in isolation, although many times they are not used correctly.

A montage compresses time. It should be used to show a series of events like a training sequence or a couple falling in love in shortened screen time.

Baby (Ansel Elgort) Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures

Edgar Wright uses quite a few montages in Baby Driver. Here’s one:

‘DEBORA’ ON REPEAT MONTAGE:

The song scores Baby’s night.

– Baby flicks through an address book. Empty except for ‘D’.

We see ‘DOC’ and his phone number written in a scrawl.

– Baby adds the name ‘Debora’. Under, he draws a question mark.

– Baby plays dialogue on his recorder in time with ‘Debora’.

BABY (ON TAPE)

Can I come with you?

DEBORA (ON TAPE)

Yes, you can.

VEEEEEP. He rewinds this. Plays it again.

– Baby uses a twin deck cassette recorder to edit dialogue.

We see stacks of TDK D90s and TDK D30s audio tapes.

– Using the pause, play and record buttons on the twin deck, he

has edited a conversation with Debora to say –

And more.