What’s your legacy? It’s a question we all are faced with, whether we choose to consider it or not. And it’s at the heart and soul of The Piano Lesson, a film directed by Malcolm Washington, co-written by Washington and Virgil Williams.

Based on August Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1987 play, the story revolves around the Charles family and their heirloom piano. Headstrong siblings Boy Willie (played by Denzel’s son John David Washington) and Berniece (Danielle Deadwyler) are embroiled in a fierce battle over the future of the family treasure, with one intent on selling it and the other just as determined to protect the invaluable symbol of their heritage.

As they continue to argue while other family members such as their uncle Doaker (Samuel L. Jackson) attempt to simultaneously mediate and steer clear of the sibling war, figurative and literal ghosts from the past surface to complicate the drama and drive home the significance of their history.

Virgil Williams

Creative Screenwriting spoke with Virgil Williams about the making of The Piano Lesson and the universal questions that underlie its simple, but profound story.

How did you become involved with this project?

It started for me in the summer of 2020. The only family besides my own that I saw was the Washington family. I was writing a film that Denzel directed called A Journal for Jordan. He really mentored me during that process and it was during that time that he and Todd Black approached me about adapting The Piano Lesson. Soon thereafter, he said that his son Malcolm had a real vision for it and asked what I thought about working with him. That act of trust, father to father, was very powerful and profound to me. Malcolm and I connected soon after and started doing the work, so that’s when it really started.

How did you approach the process of adapting August Wilson’s play?

Malcolm and I left town. I have a little place out in Palm Desert, about a half hour east of Palm Springs. We would go out there and sequester for days at a time. Netflix was very supportive throughout the whole process, they even sent us to New York to listen to the table read for the Broadway production. We also went to Pittsburgh to do research on August Wilson, see his house, so on and so forth.

But when we started the actual writing work, we went away. The first real stage is something I’ll call immersion, because you really have to immerse yourself with the piece, distill it. If it’s an engine, you’re taking it apart so that you can figure it out. This process happened in chunks of days since we couldn’t just stay out there for months.

Once we figured out a big picture of what we wanted it to look like, a sort of “wish list picture”, it was then that we could really go in and elevate it. Especially since it’s August Wilson. We found the real challenge was how to stay reverent and how to keep it what it was. Because it wasn’t broken, we wanted to elevate it to cinema.

Architect I.M. Pei put the pyramids right in the middle of The Louvre, and he did it about the same time The Piano Lesson was written. He put in this perfectly symmetrical, beautiful structure, and what did that do? He allowed for more light to come in, and for a different way for people to be able to interact with it.

We kind of did the same thing, and it was freeing in a lot of ways. We knew we wanted to leave something behind for future generations. Everybody that looks at The Louvre now is going to think of those pyramids too, they’re one and the same. So in making this play into a movie, we were aware of the opportunities there. We leaned into a lot of things, changed where we could and did the work where we could.

You not only had the blessing of Wilson’s widow, but also her involvement in the project. What was that like?

It is very empowering. I think it’s a dream scenario for any person who’s trying to make a creative endeavor. It allows you to use craft and talent and skill because you have that kind of support. There are always parameters within the creative endeavor that have to exist. But I felt nothing but supported and it didn’t feel like uphill work. I’m not saying the work wasn’t hard, but we all did it together.

The Piano Lesson is the fourth of ten books in Wilson’s Century Cycle Series. Did you need to dive into some of his other works as well to gain a bigger picture view or do they all stand alone?

They do stand alone; you could watch one or read one without knowing anything about the others. They have their own sets of characters and their locations are not all the same. But we knew that this was part of a link in the chain. We knew that this was the third produced film and that there are going to be more. So we tried to run our leg of the race as well as we could and really make it its own thing. That’s why we leaned into the genre elements that we did, and the beginning and ending are our collective creation. There was an opportunity to elevate it and invent cinema ties, so we tried to take advantage of that.

I think genius is not always complex.

A lot of times genius is genius in its simplicity

Tell me about the dynamic of the sibling relationship between Boy Willie and Berniece. How do you see their relationship?

The conflict upon which the entire plot rests is super simple because it’s entirely balanced. It’s entirely symmetrical. Right and wrong doesn’t apply to Boy Willie and Berniece, because they’re both actually right. They both have a point. I think the symmetry in that construct is the reason I.M. Pei could put pyramids in it. It’s the reason that we could find “cinematic availability” in the play, as it were, and make it into a movie.

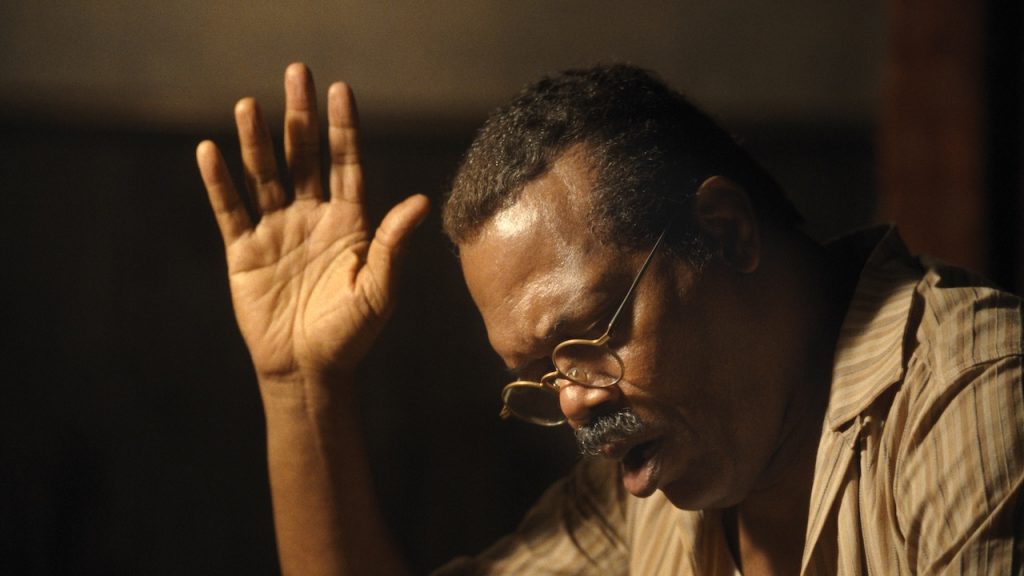

Doaker Charles (Samuel L. Jackson). Photo Courtesy of Netflix

What does Doaker’s character bring to the story?

We tried to be very conscious about how you meet people, where you first encounter them on the page. When we meet Doaker, he’s about the house. He’s taking care of the home and is the glue; the “Elder” sees a bigger picture and has a deeper history and a deeper connection. He was one of the people who stole that piano, so I think he gives you that older glue that we could all only wish for in a family.

Tell me about some of the themes you explore, such as identity, legacy and storytelling.

It’s all of it. I think those themes are what make this piece timeless. Again, it’s that genius of simplicity that August uses these themes. He crafts a story that exists within the African-American diaspora, but it doesn’t matter where you came from. You can totally relate to this story, because it’s about these things that all of us deal with. Identity, inheritance, legacy… it all boils down to the question, “What are you going to do with your own history?” It’s the question that we’re all faced with, no matter where you come from, no matter who you are. What are you going to do with your own history? Are you going to let it stop? Are you going to let it empower you or are you going to monetize it? Are you going to ignore it?

When we meet Boy Willie, he’s pushing his truck, this thing that’s going to take him to freedom. When we meet Berniece, she’s in a sleeping state. She’s ignoring that piano. It’s a question that is eternally human, all day today and then again tomorrow.

Maretha (Skylar Smith) Photo by Brian Douglas/ Netflix

Tell me about the supernatural element of the story, and the purpose of Sutter’s Ghost.

It was again, one of those pockets for cinematic availability in theme, vision and sound… all of the tools that you use to make a movie and make people feel. It was a big vein of opportunity and the thing that I think both me and Malcolm agreed immediately on – the power and the opportunity of it. August messed with genre and had his foot in those waters in terms of tone. It was already all there so there was that availability to grow it and use it. It’s been such a thrill to watch audiences respond to it at the film festivals in Austin and Toronto. People applauded. There’s this notion of trauma and it’s not the first time that horror stories have personified it and asked you to suspend your disbelief in order to play out trauma. I love that kind of stuff; I can’t wait for people to see it and hope that a lot really respond to that element of this story.

What would you say the genre of this film is, if you had to name one?

You know, I think that’s the wonderful thing about it – to watch people as they consume it, watch them be confounded and not able to name the genre. But it’s family drama. This is a haunted family drama, or a family drama about a haunted piano that’s really at the bottom of it. And when you take all the ghosts away, it is about this family being confronted with the choice of what to do with their history.

Finally, tell me about the role of music in the film.

For all of the aspiring writers out there, music and sound are one of those tools that you use. We had so many different ideas about what to do in that area, and it really did burrow down to super simple directorial vision. We used picture and sound, two very simple elements. It’s like when you cook something in Tuscany and it’s just pasta and garlic. I think it’s about using these simple things, constructing them well and with care. You need picture and sound and performance. Paul Thomas Anderson said the best set piece you have is a camera and Daniel Day Lewis. That’s the best you could ever have.

I think that’s an example of what movies are at their best. It’s picture, sound and really good performance, all made together in a way that makes for something really emotional and visceral. That’s the alchemy of movies right there.