“I was particularly interested in writing comedy,” says Paul Lieberstein, who is best known for playing Toby on The Office, but has writing credits for King of the Hill, The Drew Carey Show, Ghosted, Space Force, and now, Lucky Hank. “In my twenties, I learned there was a whole industry there, and you can do that, because I had never met anyone who had.”

Aaron Zelman, the co-creator of Lucky Hank, also realized he enjoyed writing at an early age, even though he didn’t feel he was particularly good at it back then. “It dovetailed with my interest in theater, acting, and improv. The more I did it, the more I wanted to be the one creating what I was doing.” Zelman’s additional writing credits include Law & Order, Criminal Minds, Damages, and The Killing.

Together, they adapted Richard Russo’s 1997 novel, Straight Man, into Lucky Hank which stars Bob Odenkirk as William Henry (Hank) Devereaux, Jr., and Mireille Enos as Lily Devereaux .

As an audience member, you can see both writers’ styles in the latest project. Lieberstein is known for comedy and Zelman known for darker projects. “It’s certainly easier [today] to get an audience on board for unexpected turns – dark turns, light turns, that turns away from what you’ve been watching. I think audiences are more accepting of that.”

The writers say the book is hilarious, but also very serious. “There are some darker, underlying currents of what defines the character of Hank and we didn’t want to shy away from that.” Lieberstein adds, “Something we had to talk about a lot was the storytelling demands of the episode hour. We just wanted to do people that are living, without ‘soap stuff,’ or overarching concepts. We were stretching the boundaries of how little we could do, knowing we had an obligation to keep people interested.”

To find this balance, the writers say they rewrote every single episode about four times. “The thing that we kept coming back to is doing as little as possible. We didn’t want to throw in a murder. It was a challenge to keep the audience entertained without doing that stuff, but in my life, things feel pretty damn dramatic without a murder to solve. We wanted to have an audience go on that ride too.”

To encompass all of this in one idea, the writers came up with the story drive, “The high drama of everyday life.”

Bob Odenkirk as Lucky Hank

Once actor Bob Odenkirk got involved in Lucky Hank, the writers say Hank’s overall worldview became more clarified. “Hank is more cynical than us, but he’s relatable. People are always trying to sell you a lot of crap and Hank doesn’t like bullshit. And, to joke your way through life is a very valid way to go through life, for him. He’s a fun character.”

Hank, the character, was dealing with unresolved childhood problems, problems at work, problems at home, problems with his father, problems with his mother. All of these led to other problems with his daughter, his wife, and his best friend. “It felt more real than most of the conflicts we’ve given to characters before. Things we all embarrassingly deal with all of the time.”

Zelman says, “We talked about this one theme we wanted to explore, which was how the relationship with your parents kind of never ends. You can be 50, 60, or 70 years old and it still affects you. That is embarrassing sometimes, as a full grown human, to admit you still want to impress your parents and still want that approval. It’s very real.”

In the story, Hank seeks his father’s approval, but also despises his father for leaving their family. From an outside perspective, the literary world respects his father more than they perhaps respect Hank, a novelist turned professor. This also shows up in a somewhat lost friendship with the characterization of author George Saunders in episode 2.

Hank Devereaux (Bob Odenkirk) & George Saunders (Brian Huskey). Photo courtesy of AMC Networks.

“These professors are very smart and were very ambitious, at one time, in their own ways,” Lieberstein says of the college professors. “Each one of them is disappointed in a way. They’re not just satisfied, so we thought we could bring someone really successful to the campus and see the crisis it puts them all in.”

The George Saunders Character

The original idea would be to create a fake character based on George Saunders, but they decided to reach out and surprisingly, the author liked the idea of using his name as a character on the show. Brian Huskey (VEEP, Childrens Hospital) stepped into the shoes of the iconic novelist of Lincoln on the Bardo and Tenth of December for the show. “We talked to him directly, gave him the script, and he had some thoughts about his dialogue. It was amazing.”

Once Saunders read the script, he actually offered some touch-ups in the dialogue. “It was inspiring, actually,” says the writers. In the episode, Saunders was there to speak at the campus and also sat in on one of Hank’s classes where he provided students with some notes and motivation, something Hank typically avoided in his day-to-day life.

“We gave him the final draft to sign off on. We did ask him if he wanted to play the part. He says he was 80 percent sure he wasn’t going to do it. We were like, ‘Really, so there’s a chance?’” In the end, he decided not to do it, but the characterization of Saunders certainly enhanced all of the fictional characters on the show.

For Hank, he only needed to come to one realization for the show to work. “That’s the work of it. This realization that people get don’t come around very often. It takes a season to build to one,” says Lieberstein. “We let him have that time. Then, I don’t even know if they stick. We have these realizations, but we can’t fix ourselves. But it helps for a little while.”

TV is more like the rhythms of life. It’s not a straight line.

Two of the staff writers on Lucky Hank also wrote for Mad Men. What Zelman appreciates about Mad Men is that Don Draper has realizations, but then goes back to his old self. “I found that to be a very real way of storytelling. It’s a nice way to remind myself that no matter what we do with a moment of self-awareness, it doesn’t mean we can’t convert or fall back. That character doesn’t forever have to be changed, unlike in a movie. TV is more like the rhythms of life. It’s not a straight line.”

What’s Your Driver?

Lieberstein says he was less familiar with hour-long dramas, but one thing that helped him get a grasp on it was the idea of, “What’s your driver?” In other words, “We wanted to know the comedy drivers, but those are character things, so the hour-longs have story drivers. Is it a procedural or what can you do every episode? We wanted to find it with character which was pretty challenging.”

For both writers, it’s also important for comedic moments to display character. In one particularly odd moment, Gracie’s (Suzanne Cryer) notebook essentially pierces Hank’s nose when she slaps him with it, but even in pain, he can’t help but insult her. “Let go of the notebook,” he tells her. “It has original work in it,” she replies. “Not if it’s yours,” he tells her, causing her to rip a tear in his nostril.

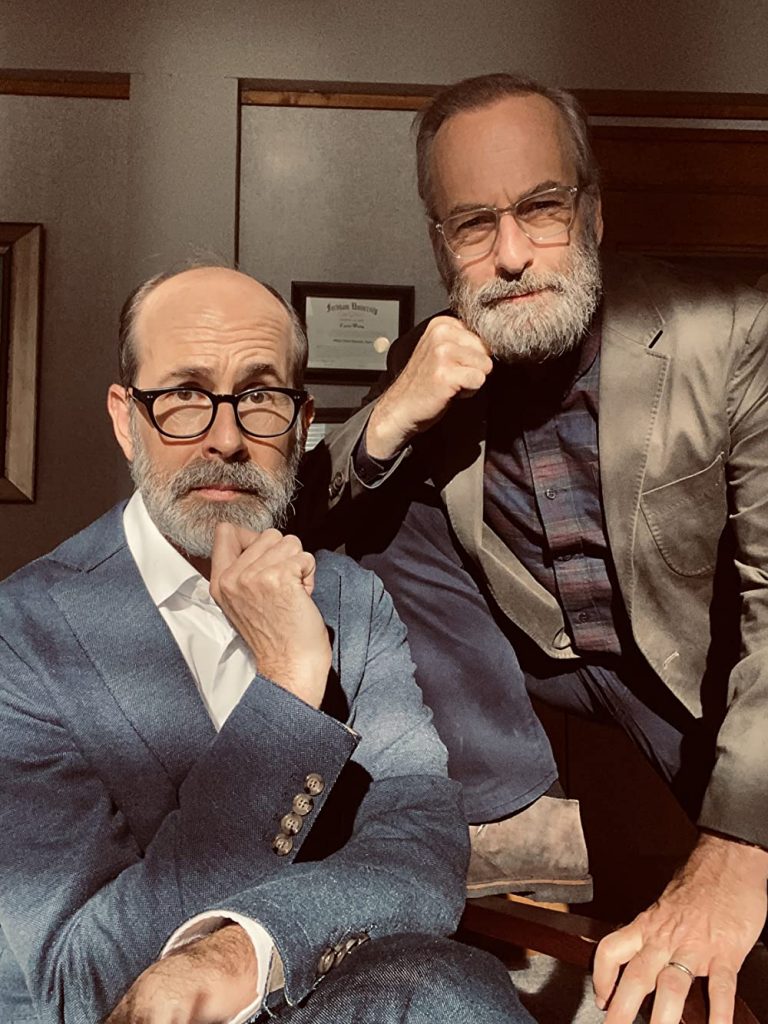

Aaron Zelman. Photo by Photo by Corey Nickols/ Getty Images

“The event itself is from the book,” says Lieberstein. “The smack. Some of the dialogue is ours. But it was that character and he was teasing her about her poetry. There’s some stuff that was visual in the book that we had to kind of take a beat on. Is this going to play? In the book, he also strangled the goose. We knew everyone would hate us, it wouldn’t be comic, so we had him box the goose with no actual contact. The notebook was also a bigger injury in the novel. We didn’t want to have him with a big bandage for eight episodes.”

The writers used the book to create tent poles for the plot. “So much was trial and error. The first thing, we sat down and thought about a chapter an episode, what would that look like? I’ve adapted a bunch of novels,” says Zelman, “and I learn the same lesson every time: novels are not TV. The demands of television have so many story demands. You have to create so much more story. But in the end, we ended up using more from the novel than we thought, then the little stuff in between was invented.”

Staffing the Writers’ Room

For this show in particular, the writers wanted a handful of people who understood academia, since this is where the bulk of the characters lived and worked. “We found two writers and they were both relatively new to writing TV. There was a lot of reading. When you’re staffing a show, the first thing you think of is your go-to people, who would be perfect, who you might want sitting next to you.”

From here, they went out to look for a combination of people with experience and unique voices. In some ways, of course, the industry has changed, so many of their go-to staff writers from previous jobs have gone out to become showrunners or create their own shows. Zelman says, “Sometimes people [work with you] as a favor between gigs, if there’s a slot. That’s the case for anyone who has been around. Then, we have to be introduced to staff writers through agents and producers.”

In situations where a spec script stands out to the showrunners, it’s often something intangible that sparks their interest. For Lieberstein, he may say to himself, “Oh, I wish I wrote this.” He says, “That’s the biggest thing, but sometimes it’s a little thing, like a joke making me laugh. That’s hard, so if someone can do that 2 – 3 times in a script, that’s someone worth meeting.”

“The thing is, you read a lot of good stuff, but once in a while, you’ll be surprised. I love to be surprised. If it makes me laugh in a way I didn’t expect or surprise me with a story or character turn, something I haven’t quite seen. That’s what really stands out to me,” says Zelman.

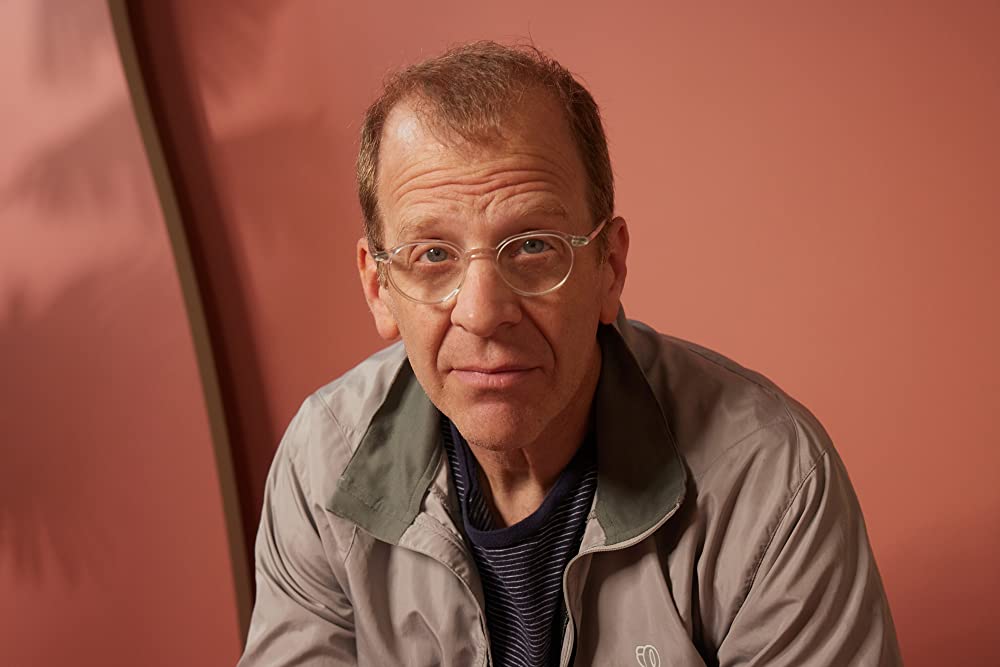

Paul Lieberstein. Photo by Corey Nickols/ Getty Images

As for false beliefs the writers had early on, Liebertein says, “I was absolutely convinced that the best ideas will rise to the top and all you have to do is offer them and they will sell themselves and write for themselves. And no, you have to have good ideas and not just have them, but be good at fighting all the way onto the air.”

“This job,” says Zelman, “is Death of a Salesman. We’re salesmen. We’re Willy Loman and we have to convince producers, studios, networks, actors, that this is the thing they should do next, out of all of the other hundreds of projects they have. Why should we do yours? And that’s what you have to do. You have to want it to happen, more than ever in this business, and that’s the reality. There’s a lot of good stuff, but you have to convince people you are going to carry this through and not give up on it.”

This interview has been condensed. Listen to the audio version here.