by Ken Droz

“Hey guys, I have to run over to Elmore Leonard’s house for a bit, so I’ll be back a little later.” Those were some envied words, admittedly, spoken to my co-workers 25 year ago on the day I first met Elmore “Dutch” Leonard. I was picking up the script of a film he wrote, an adaptation of the best-seller, The Rosary Murders, which our marketing agency was promoting.

Upon arriving, we chit-chatted a little, about the film and the script, but I could see he was working, and didn’t want to stay long. But when he invited me to sit down for a minute, I didn’t have the heart, or for that matter, idiocy, to say no. He then explained he was on page one of his new book, Killshot, which he was writing long-hand—yes, long-hand. (“A pen connects you to the paper. It definitely matters,” he once told Esquire magazine.). He wrote on the same un-ruled yellow legal pads he used to write short stories on, at his day job writing ad copy in the ’50s, where he would write the fiction in his desk drawer, hidden from co-workers. That day I certainly didn’t want to hold the man up, but we ended up chatting for an hour, as he voluntarily explained the book’s beginning, the characters, his approach, etc. and then… who knows. He had no outline, and no idea how it would end, and liked it that way, usually. If he got bored with a character, he would just kill him off. No wonder Hollywood so often didn’t know how to translate his work to the screen.

Sitting on a bookshelf behind me, in a printer’s box, was the manuscript for his book Freaky Deaky, just completed, ready to be sent to the publisher. One up. One down. If, as Tolstoy said, transitions are the most important part of writing, then I was witnessing a world-class example. For as talented a writer as Elmore Leonard was, his work ethic helped propel him to the top, writing practically every day, 10 AM to 6 PM, with barely a break, even to eat. Similar to Woody Allen, he would turn out one book every year. Astonishing.

A creature of habit, as most writers are, if you wanted to contact Elmore, aside from snail mail, you had to call him on the telephone. You see, Elmore not only didn’t have email, he didn’t even own a computer. If too immersed to chat, he just wouldn’t answer the call. While he did have “people” to handle stuff like typing (his daughter Jane) and his website (long-time researcher and go-to guy Gregg Sutter), you had to admire the purity and liberation of his avoiding today’s electronic noise. Especially for a writer, when keeping your head clear of that stuff is so crucial.

Since our marketing agency worked for most of the major film studios, I got to invite Elmore to advance screenings of loads of other films, affording multiple opportunities to chat or catch up, creating an actual friendship. Then, during one phone call long ago, he said, “Hi Ken, it’s Dutch,” providing me the opening to call him by that same nickname, an honor both elating, and, like the man, quite casual. You see, whenever he entered a room, it was never Elmore Leonard the celebrity walking in, revered by millions of fans throughout the world. It was just the always unassuming Dutch, an amiable Detroiter who would chat with whomever, about anything, as if he knew you for years. If it was about writing, or movies, fine. But he was just as interested in how the Tigers were doing as the next guy, no matter how many calls came that day from Steven Soderbergh or George Clooney (Out of Sight) or Quentin Tarantino (Rum Punch/Jackie Brown) or Timothy Olyphant (Justified).

That closeness with Detroit certainly helped inform Dutch’s acuity with crime, given his many ride-alongs with Detroit’s finest, and relationships with real cops and homicide detectives. But then, Detroit certainly didn’t inform his creation of the book Cuba Libre, set during the Spanish–American War, or those early Western novels that launched his career.

Working closely with and becoming friends with guys like Dutch, and other resident stars like Jeff Daniels, or Mitch Albom, you are often asked to play the role of Clark Kent, as the only person around who can get to Superman. When coordinating a film publicity tour years ago for a low-budget horror film, the film’s up-and-coming director even made that same request as soon as she got off the plane. “Elmore Leonard lives here, right,” she said. “Is it possible I could meet him, for lunch or something?”

“Well, let me call him, and find out,” I told her. And, at a moment’s notice, Elmore was all too willing to accommodate the woman, a then-unknown Kathryn Bigelow. He would do that often, giving his time to various requests from either strangers or locals who had a good cause, panel discussion or benefit.

One of the great examples of this was when Elliot Wilhelm, film curator of the world-class Detroit Institute of Arts, made the winning bid at a charity auction to have his name used in Elmore’s next novel. Mr. Wilhelm, an erudite, diminutive fellow, and a film scholar of the highest order, was surprised and amused (as we all were) when Be Cool was published, the sequel to Get Shorty. It featured an ominous, 260 lb. bodyguard, who was gay, named Elliot Wilhelm, portrayed in the feature film so nicely by Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

While movies have been made from his work for years, Hollywood’s track record was also erratic, especially since his protagonists are not always good guys, nor were his stories wrapped up in typical happy endings. His characters could be hilarious in their ineptitude, hostility or futility, but they certainly don’t know it.

The watershed point was when stellar screenwriter Scott Frank succinctly cracked the Leonard code in adapting Get Shorty and Out of Sight. After a long time, Elmore Leonard was suddenly a very hot Hollywood commodity, as studios, producers and Quentin Tarantino were optioning practically every book in the Leonard canon. Some got it right, and some did not, and many projects are still unmade, which is natural. Like years ago when one studio paid heavily for the rights to Cuba Libre, and then paid the Coen Bros. $1 million to adapt it, only to throw out their draft when they received what might be called a typically hard-to-categorize Coen Bros. script.

I asked him, incredulously, “Well, what were they thinking? It’s the Coen Brothers.” He just laughed, and said, “That’s what I said. But that’s Hollywood.”

It was a while before I revealed to Dutch I was also writing screenplays. He never rolled his eyes, like ‘Here’s another naïve sap,” but was supportive, and open to discussing the craft as he would with any writer. And believe me, discussing writing with Dutch Leonard was like talking baseball with Casey Stengel or Ted Williams. Right before I moved to Los Angeles 14 years ago, he invited me over for lunch, to discuss the industry, writing, or anything else that came up, and offering words anyone would die to hear: “So, what can I do to help?”

While I lived in L.A. he would arrive on book tours, or for premieres, and he would be his usual gracious self, meeting up at Kate Mantilini’s after a speaking gig, or leaving tickets to a premiere party, always curious to know how things were going for me.

A few years ago family circumstances necessitated my moving back to Michigan, where I now live just a few miles from his home. With great pleasure recently, I informed him I was hired to write a script, adapting a prominent non-fiction book. He was extremely happy for me, and in a split second made the razor sharp suggestion of a slight title change. Initially hesitant, I realized he was right, especially after testing it amongst friends, who all agreed emphatically. And no, I was not shy in later revealing to them the source of the great new title. While Elmore was so renowned for his highly original characters and dialogue, he was also a master of story. When discussing a script of mine once, he made a suggestion that shed a whole new light on things I hadn’t even considered. Another master class lesson, at no charge. Thank you very much Dutch.

Given how his legacy had been firmly established, earlier this year I suggested to some public television contacts of mine a documentary film on Elmore that I would co-produce. It was to be a potential project for PBS’ esteemed American Masters series, which drew Dutch’s interest and appreciation, as he took us to a nice dinner to discuss it.

At the time however, Elmore was also coming off a difficult divorce, and was deeply behind on his latest book. He soon realized he needed to focus on that first, unfortunately, before taking on any other distractions. The only thing he would interrupt writing for was a public reading with his son, novelist Peter Leonard, of whom he was so very proud. He laughed when I compared him to hockey legend Gordie Howe, who famously got to play professionally, finally, alongside his two sons Mark and Marty. Elmore was apologetic for the withdrawal, but also pained in explaining why he had to table the project. At age 87, he was slowing down a bit too.

Elmore Leonard was a writer, through and through, and would write until his end of days, the thought of retirement never entering the conversation. In citing Philip Roth’s recent retirement, we both laid very low odds on his eventual ability to stay away from the keyboard. Because that’s what writers do, they write. Not something one aspires to as much as they are compelled to do, drawn by a force that is just inexplicable.

Which is how Elmore explained his having to defer the documentary. He had been unable to work on his book for months, and it was killing him. “I have to write this book, Ken. It’s what I do.”

And, my God, who could argue with that.

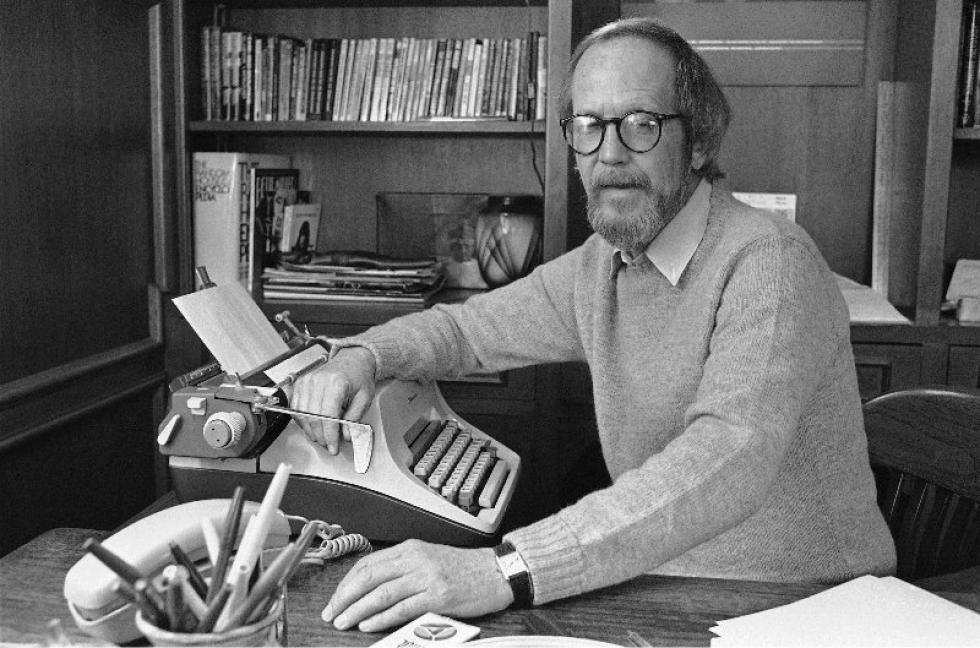

As I type this into my computer, yes, from a first draft written long-hand, I keep on my walls two inspirations. One is a photo of Kurt Vonnegut, looking serene, as he leans on his typewriter. The other is a framed Get Shorty poster Elmore autographed for me just before I moved to California.

It says, “To Ken. Be Cool. Elmore Leonard.”

I will try, Dutch. I’ll sure as hell try.