- Scene Stealers: Writing The Perfect Heist (Part 1)

- Scene Stealers: Writing The Perfect Heist (Part 2)

Unbeknownst to them, a silent alarm has already been triggered by a quick thinking teller, there’s an off duty police officer in the queue waiting for a chance to reach for his ankle holster, and the safe is empty.

There’s a reason why heist films exploded onto the scene during the infant years of filmmaking. It’s the heart pumping action, the suspense that keeps us enthralled, the high stakes, the shady characters — that have us routinely coming back for more.

In 1903, the silent film The Great Train Robbery quickly became popular with audiences for its fancy editing and wild stunt work. The popularity can also be rooted in the romanticization of lawless bank robbers and wild west bandits popularized by the media at the time. Butch Cassidy was very much alive and causing havoc in real time.

Over the years, our interest in death defying capers has remained constant while the very art of the heist has evolved. Technological advancements in security and law enforcement, as well as socio-economical factors, have made it more difficult for criminals to pull off successful capers.

The same is true for the screenwriter planning to write one. So what are some of the common elements found in all of your favorite heist films that can help you plan your own?

The Leader

The heart of every heist film centers around a protagonist that the audiences can empathize with and root for despite their criminal backgrounds. Whether it’s their charisma or motivations, we want them to succeed even though their actions go against our moral reasoning.

Thieves are often glamorized in the media, creating narratives that garner sympathy for outlaws like Bonnie & Clyde despite their real world terror. We’re talking about criminals who killed innocent people in their pursuits of infamy, yet many people facing The Great Depression head on could understand why they’d resort to such drastic measures. They saw brave rebels fighting back against the very forces trying to take their livelihoods — not cold blooded killers.

Myths are created about the leaders of notorious criminal enterprises. Butch Cassidy, Jesse James, and like Keyser Söze in The Usual Suspects, the leader is often the one spinning the tale and setting the heist in motion. Of course their cause is noble, they’re the ones telling it. The mark doesn’t deserve what they stole in the first place.

How can one root for someone who is responsible for doing bad things?

There needs to be a justifiable reason.

The Reason

There’s a Robin Hood dilemma at play here in that the protagonist is breaking the law and hurting people, but it’s portrayed as a means to an end that audiences can ultimately agree with. There needs to be a reason or rationalization for their theft. Often in these scenarios, the thief is someone who is forced to go to drastic measures by an oppressive force. Still, they have underlying morals and standards.

Usually the antagonist (a fellow thief, the bank, or class/power structure at large) takes something away from the protagonist and the protagonist has to reclaim what was stolen from them. This gives justification for their actions to a limit, which is usually tested when things go awry, a member of the team makes a mistake, or someone gets killed.

The reasoning and rationalization of accepting the leader’s criminality is dependent on what’s at stake. The heart of the heist.

The Stakes

What will the character lose if they fail to pull off the heist? What will they gain? Is it simply about greed or a higher purpose? The reason gives rise to the stakes and ups the ante when complications inevitably arise.

Success for the protagonist has to be about more than just money. Sure, financial freedom is awesome — but what do they really gain?

There have to be real stakes. Will this one last job free the protagonist of their debt to a notorious gangster? Will it allow them to see their children again like in Inception?

Armed robbery is a life or death practice. Going into it, the stakes are already high. Adding an extra layer of motivation creates depth to your character and allows audiences to relate to them. It provides a reason to root for them.

The same way you should consider the success of the heist, you also have to be aware of the consequences. What happens if they don’t pull it off? Will they return to prison for a crime they didn’t commit? Will their family be killed? Will our hero become a fugitive?

Determine the ramifications for success and failure and make sure the audience knows what hangs in the balance. The stakes make the situation real.

The Team

To get through all the layers of security, the leader’s going to need a trusted team of shady characters to help him break through.

The supporting characters of a heist film each have a specialty that they bring to the table. There are variations of assembly and sometimes multiple archetypes are lumped into one character, but they tend to serve the same purpose across the genre. If your protagonist doesn’t fly solo, the team can be anywhere from 2-13 characters.

- The Leader/Mastermind – The only one brave (or dumb) enough to pull this off. Examples: Ethan Hunt (Mission Impossible), Danny Ocean (Ocean’s Eleven), J. Daniel Atlas (Now You See Me).

- Partner In Crime – Could be a lover, sibling, friend. This is the person who knows the leader better than anyone. They’ve likely pulled off heists together before and are more than ready to help again. Sometimes acts as a wild card. Bonnie & Clyde, Tanner Howard (Hell or High Water), Linda (Widows).

- The Backer – They are the boss behind the operation and usually organizes and/or plans the heist for the thieves for a fraction of the haul. They provide the means for the thieves to operate. Think Joe Cabot from Reservoir Dogs or a criminal organization.

- Hacker – They’re the ones with the codes, can unlock doors from afar, or crack open a safe with a homemade gadget. Their greatest weapon is their brains. Luther (Mission Impossible).

- Conman – Smooth talking and a master of disguises, this character is able to sneak or speak his way through any obstacle. Often the comedic touch.

- The Driver – Entire films have been made based on the driver. The chase sequence is an integral to most heist scenes and the make or break moment when the heist will either succeed or fail. The driver often has the most important role. Driver (Drive), Baby (Baby Driver).

- New Kid – Sometimes the new kid is our way into this world of criminality. Other times the new kid becomes a liability. Regardless, it’s hard for others to trust the new kid when he hasn’t proven himself yet. Fodder for endless jokes.

- Inside Man – These are the characters who have ulterior motives to sabotage or thwart the heist for their own personal gain. They can be moles, undercover detectives, or pulling a double caper. Examples include Mr. Orange (Reservoir Dogs), Steve (Italian Job).

The Team in The Italian Job (2003)

The Target

The target of the heist scene is a MacGuffin. It’s the element or object that everyone is trying to acquire or protect. It’s the Holy Grail, the cache of cash, priceless art, information, data, or a jewel lost to time. The target is the central engine that drives the plot forward.

It’s also located at the center of a maze of impenetrable obstacles.

Tony Gilroy talked about the importance of visualizing the location when developing action scenes. Consider the logistics and limitations of the physical space.

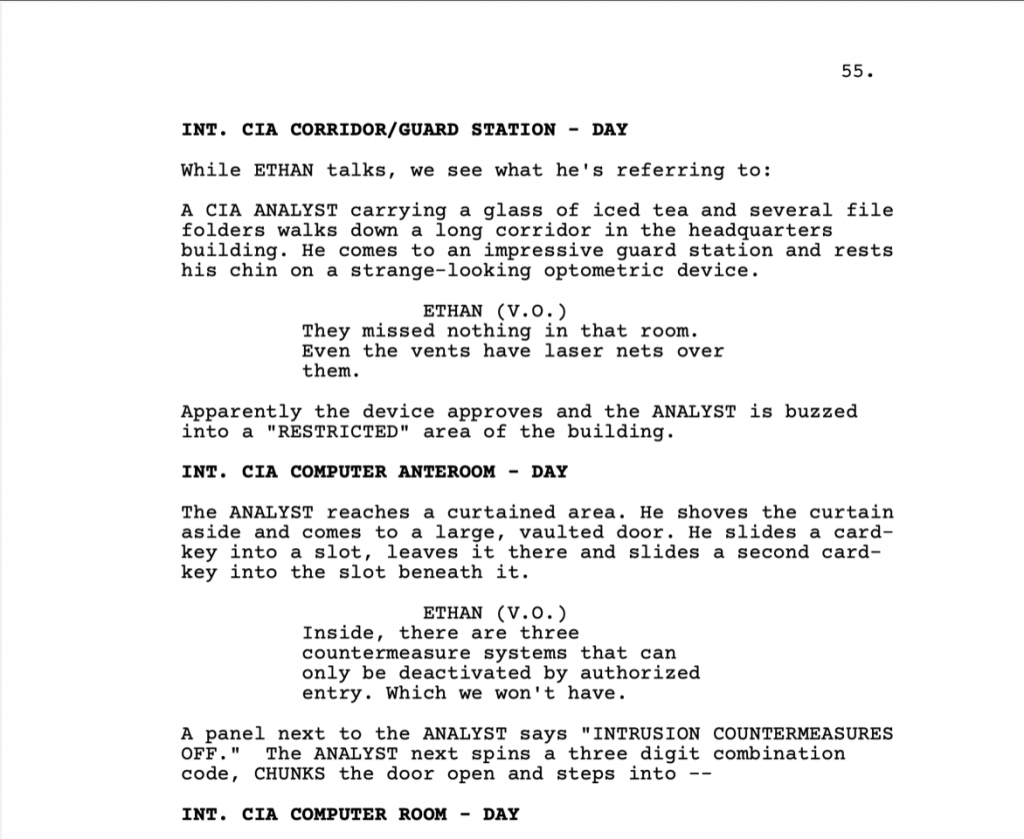

The planning scene in Mission Impossible right before the famous CIA Headquarters heist lays it all out there perfectly. David Koepp and Robert Towne set the board. They show the target and the obstacles in their way.

Even if you don’t have a scene where they walk you through all the security measures, you should still take that walk yourself. Consider how to get around those obstacles, and all the ways the plan can go wrong.

The type of heist largely depends on the MacGuffin, its location, and what the thieves need to do in order to reach it. Is it a small town bank? Shotguns and fear should work.

An armored truck, on the other hand, would need a little more brute force.

A CIA Headquarters? That requires a little more finesse.