There is something in the contemporary horror zeitgeist which fuses elements of a pure evil monster genre with a supernatural family drama. The Black Phone was initially written by Joe Hill (Stephen King’s son), so the short story was always going to ooze mood, creepiness, and dread rather than a relentless stream of gore and jump scares. Here are some extracts from the opening paragraphs:

“The fat man on the other side of the road was about to drop his groceries. He had a paper bag in each arm, and was struggling to jam a key into the back door of his van. Finney sat on the front steps of Poole’s Hardware, a bottle of grape soda in one hand, watching it all. The fat man was going to lose his groceries the moment he got the door open. The one in his left arm was already sliding free.”

“The lock popped and the rear door of the van sprang open. What happened next was such a perfect bit of slapstick it might have been practiced – and only later did it occur to Finney that probably it had been. The back of the van contained a gathering of balloons, and the moment the door was open, they shoved their way out in a jostling mass… thrusting themselves at the fat man, who reacted as if he had no idea they would be there. He leaped back. The bag under his left arm fell, hit the ground, split open. Oranges rolled crazily this way and that. The fat man wobbled and his sunglasses slipped off his face. He recovered and hopped on his toes, snatching at the balloons, but it was already too late, they were sailing away, out of reach.” This set the stage for Finney’s fate.

Robert Cargill. Photo by Jessica Cargill

Scott Derrickson and Robert Cargill (both known for their work on Sinister and Dr. Strange) expanded Hill’s thirty-page short story into feature film length by adding more familial and school life elements to it. Scott was balloon-deep in another project, so we spoke with one half of the writing team, Robert Cargill, about getting The Black Phone onto the screen – something they had both wanted to do for a considerable length of time.

There is something visceral about The Black Phone – a straight up horror story of a boy’s wits, Finney (Mason Thames) pitted against a murderous beast, The Grabber (Ethan Hawke). The Grabber has little tangible backstory in the film. The audience doesn’t fully understand what drives him to kidnap children, enticing them to escape, and eventually catching and killing them after they do. This only adds to the psychological torment he forces onto his victims.

We asked Cargill what initially attracted him to this short story. “Every element of the story lent itself to a fresh, original horror story. From a kidnapper stuck with visiting family [his brother], preventing him from killing a child, to a phone with previous victims’ voices on the other end. Every piece felt like it was a part of a larger story – exactly the kind we like to tell.”

The adaptation was one of expansion rather than a reimagining or refocusing of the short story. “We kept almost everything. It’s all so good,” exclaimed Cargill.

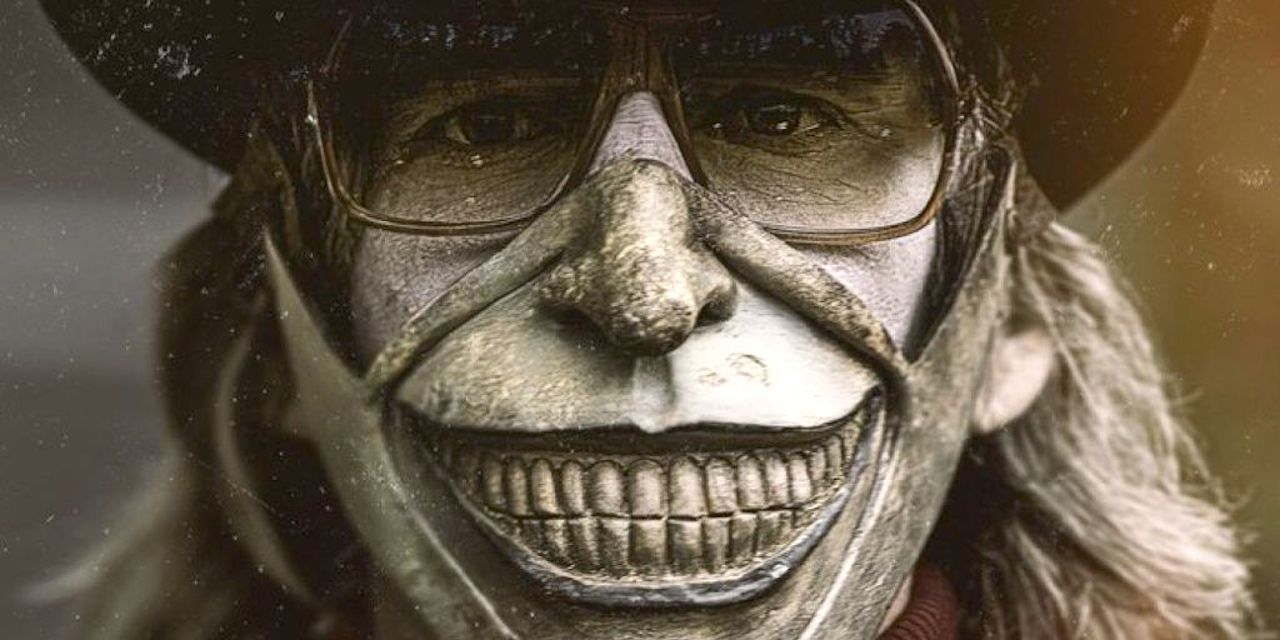

“The one major change was changing the killer from being dressed as a clown to being a magician that harkened back to the old school magician/devil stage show that would have been popular in the Grabber’s youth,” Cargill continued. The Grabber was originally morbidly obese clown with a bald head and loud Hawaiian shirt. The legacy of the balloons remained, but the magician added an eerie new dimension as they were used as a tool to kidnap children rather than delight them.

“Since the story was so short, most of the film was constructed. Everything about Finney, Gwen (Madeleine McGraw), their home life, and every ghost, aside from Bruce Yamada was our creation,” Cargill elaborated.

The retro 70s Denver setting was more than a nostalgic locale choice to set The Black Phone. “Denver was Scott’s childhood place and the primary inspiration for making the film. That was what we originally wanted to make, and then realized the The Black Phone was the perfect narrative engine for that story.”

Despite its cracking pace, The Black Phone explores prominent themes of childhood and adolescence. Finney is something of an introverted outcast at school while Gwen is more assertive, kicking the school bully where it hurts.

Finney Shaw (Mason Thames) & Gwen Shaw (Madeleine McGraw)

“The resiliency of youth is the principal theme we’re exploring in the film. But we also dip our toes into exposing the layer of awfulness that coated the childhoods of the 70s and early 80s. These are the times as we really remember them rather than sugar-coated nostalgia. Our youth was ugly, tinged by a racist, homophobic society, in which discipline was often indistinguishable from abuse. We wanted to explore that.“

The Black Phone ostensibly examines the effects of trauma. Finney and Gwen are traumatized by the loss of their mother and their alcoholic father who hates himself more than an empty whiskey bottle. So too, The Grabber is a product of a presumptive abusive upbringing. Cargill and Derrickson carefully guard his full backstory, barely tossing a few breadcrumbs to the audience so they can focus on what The Grabber does rather than the why.

“The Grabber is the child of trauma, much like Finney and Gwen. But he allowed that trauma to transform him into a monster. He has ritualized his killings, hinting at a similar, previous abuse that makes him what he is. He is a monster meant to be deconstructed, hinting at his past only through subtext and strange statements. But if you pull at the threads he leaves behind, he becomes pretty understandable.“

The Grabber’s swapping from Clown to Magician also adds another sheen of mystique and depth to the character. “It is clearly a nostalgic fixation tied somehow into his abuse as well as his attempt to relate to the children he intends to abduct,” the screenwriter continued.

The horror genre is centred on its premise of mining fear. Cargill and Derrickson didn’t just settle for the fear of death element to base their story on. “We also looked at fears of violence, abduction, as well as the ghosts on the other side of the veil all play into how we convince the audience to grip their arm rest a little tighter,” said Cargill.

The more subtle horror elements that didn’t involve blood and jump scares were gently folded into the story to give it more texture. “The sense of dread, creepiness, and impending doom was mostly done through pure cinema, but on the page, it involved a ticking clock with an end timer we aren’t a hundred percent sure of. But the key to all horror is great characters. We spend half an hour getting to know and love Finney before we throw him in that basement, and by then, you want so badly to see him get out that you feel every scrape and bruise and jump at every bump in the night,” he added.

Derrickson and Cargill spend considerable time illustrating Gwen and Finney’s physical and emotional abuse at the hands of their ineffectual, self-loathing father, Terence (Jeremy Davies), who dulls his pain with another swig of a bottle – even if it’s empty, bar a few final drops which may soon evaporate. In one scene Gwen dramatically drops a half-filled whiskey bottle to punish him as if it’s his most prized possession.

“Alcoholic dad plus physical abuse plus rampant bullying equals relatable 70s childhood. These scene were very much pulled from our youth. When you give the audience relatable touchstones, everything else will feel real too,” elaborated Cargill.

A black phone is a cornerstone of the movie – a disconnected phone that rings allowing Finney to communicate with The Grabber’s victims and hopefully guide him to freedom. Gwen has inherited their mother’s ability to have premonitions which eventually lead them to Finney.

“These elements give the characters tools to save themselves that other victims didn’t have. Audiences love to watch people fight back. And the supernatural elements do just that in this film,” said Cargill.

We asked Robert Cargill if he could identify one pivotal scene that captures the entire essence of The Black Phone. “The scene in which Gwen is angry at God/Jesus for not helping her find Finney. She has no idea how her powers work and has pinned them to religion to make some kind of sense out of them. But when they fail her, she grows angry trying to figure out why she can’t get back the most important person in her life.”

Although there are some biographical elements in The Black Phone, it allowed both Scott Derrickson and Robert Cargill to better understand their childhoods.