“When a guy I had never met called me up and said, ‘You and I are going to drive across America and I’m going to write a book called Mike Reiss’ America,’ and because my mom always told me ‘Take rides from strangers,’ I said, ‘Sure.’”

The original ghostwriting assignment didn’t pan out. The duo pitched the idea about the assignment, which didn’t include any Simpsons material, but six months later, a different book came out. “It’s 98 percent Simpsons and I never rode in a car with this guy anywhere,” he joked.

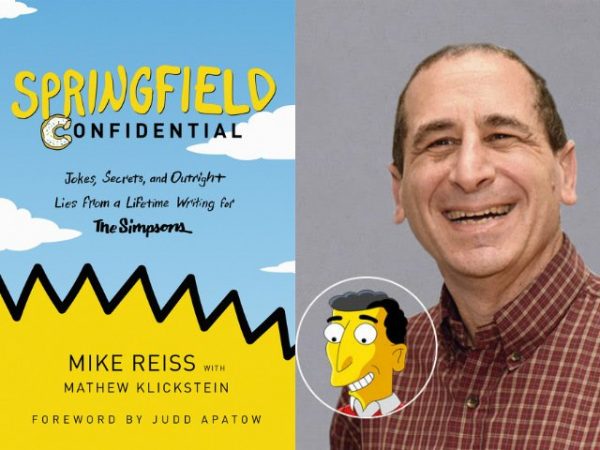

Ironically, Reiss said he never would have agreed to write a memoir about his thirty-year journey as a The Simpsons writer, but once the words started flowing, Springfield Confidential was the result. “It’s not just a book, it’s a distillation of thirty years of lectures.”

A (Mostly) Drama-Free TV Writers’ Room

Reiss’ book isn’t exactly a tell-all, but this is because there’s nothing to tell. “The amazing thing about The Simpsons is that in thirty years, there were literally two scandals: One was ongoing between the two creators – Sam Simon was resentful of Matt Groening getting all the credit – and five years later, we had a bad day and a half where we wanted to do an episode and Matt Groening didn’t want to do it. That’s the entirety of it. That’s all the dirt.”

After writing the book, Reiss thought in hindsight that the confrontation-free TV Writers’ Room is perhaps “one reason for The Simpsons’ success.” He added, “There is no dirt. There is no friction. It’s very rare in television that everyone is pulling in the same direction. Everyone is trying to make the best TV show they can.”

“This is how Monty Python operated, too,” he added. “There’s really no friction there. These guys were friends all the way through. They respected each other’s work and there’s no dirt. This is also true for the show, M*A*S*H. Again, a long-running, beloved show with no fighting.”

Bart Simpson, Al Jean & Lisa Simpson

“I spent the first 16 years of my career with a writing partner, Al Jean,” said Reiss. “You’ll hear nonsense about comedy writing teams where one guy is structure, one guy is this, but Al Jean and I think 90 percent the same. We are very similar. When one of us pitches a joke, the other says, ‘I was about to say that.’ You don’t need friction. Most TV scripts from comedy teams are a draft ahead. A comedy team’s first draft reads like a single person’s second draft.”

“The problem with shows that run this long is that you have to keep topping yourself. Itchy and Scratchy had to get more graphic, to the point we almost never do another Itchy and Scratchy. The same with Bart’s prank calls to Moe’s. How do you make that more clever? You have to amp things up and get so crazy just to keep from repeating yourself that it’s not the thing anymore. That’s pressure.”

To make a good season of The Simpsons, there needs to be a variety. “We have the purely funny, the purely heartfelt, and everyone has their specialty. At this point, we have about 20 writers and do about 20 episodes a year, so that gives every writer one shot to shine, make it personal, but the script will be rewritten over and over again. That’s the process.”

In addition to Reiss’ book, Springfield Confidential, the screenwriter also highly recommends reading Poking a Dead Frog by Mike Sacks for individuals looking to write television comedies. “I love everything about the book except for the title,” he said about Sacks’ book. “It’s a college education about TV writing.”

Finding Value in Fan Criticism

For the last three decades, the screenwriter has been talking about the show and answering fan questions. Reiss said, “You rarely read a book where every joke in the book has been tried out in front of 50,000 people.” But, in addition to refining his own material, the creatives behind the show also look for the small amounts of good advice from fans, amidst the chaos of the often-negative Internet comments.

“Our fans – I call them our fans even though they’re brutal about the show… No one at the show reads [online comments] anymore except Al Jean, the man who has been running the show for twenty years. Al will go there week after week to see our fans crapping on the show.” Reiss then gave a particularly harsh example. “This tells you everything about Al: he was in a horrible accident and still managed to get to work. I think he tweeted that and one of our ‘fans’ wrote, ‘I wish you had died.’”

Regardless, Jean continues to sort through the cesspool because “every once in a while, they’ll make a good point. If a point comes up a lot, he knows it’s worth listening to, like people really hate when we make Homer too jerky, too mean. They call him ‘Jerk-Ass Homer’ (this was one of the original criticisms of The Simpsons Movie) and we’ve tried to alleviate that.”

“To Al’s credit, who is the hand at the tiller, we don’t get complaints anymore. For years, this is what I put myself through. When I would lecture, the first question is always, ‘What do you say to people who say The Simpsons has gone downhill?’ Which is a real chicken-way to ask the question.” He continued, “They’re not saying, ‘Why has The Simpsons gone downhill?’ You’re not fooling me. That’s like saying, ‘What do you say to people who say your sister is a slut?’ I haven’t heard that question in years, but I’ll be the first to admit that every now and then, we put out a bad decade of shows,” he joked.

How to Write A TV Show with Nothing to Lose

(How to Write The Simpsons in 21 Steps)

In the early days, the bulk of the writing staff assumed the cartoon would be canceled within the first season. As such, they started to write the show with nothing to lose. “When this show came on the air in 1989, TV kind of sucked. It was bad. I liked TV growing up – I Dream of Jeannie and The Beverly Hillbillies – these shows were colorful, but I sort of blame Norman Lear.”

Norman Lear

“He’s a genius in TV and All in the Family is the greatest television show of all time, but he made shows without special effects with three people sitting in a living room and all of TV took the bad message of that.” He sarcastically said, “That’s right, we don’t need to try at all. Just three people sitting on a couch.”

Reiss and company felt like The Simpsons could change that bad dynamic. “Then, once that worked, the show was guided more by fear. We don’t want to be the guys who screw up The Simpsons. We don’t want to ruin the show. That motivates us.”

In terms of staffing, Reiss actually borrowed part of the formula he learned while writing for the Lampoon in Harvard. “The best writers want to work on the show, so we just sift through the best writers. I broke into TV with a Golden Girls script, and now I am one! But, Al Jean and I worked so hard and made it perfect, but later we strip-mined it. The A-stories and B-stories ended up as Simpsons episodes. I always tell people, ‘Work really hard on your spec script because it’s the last piece of good writing you’ll ever have to do…’”

In the Springfield Confidential book itself, he clarified the process as follows: “The competition to get on the Lampoon operates exactly like the TV business. Students competing are expected to turn in six humorous articles in eight weeks, which teaches you to hit deadlines and to be prolific, two fundamental skills in television. Like in TV, the competition is brutal—every year, about a hundred writers try out, and only seven get chosen. And finally, just like in TV, the process is completely unfair.”

Years later, Reiss was in charge of running The Simpsons (he also ran The Critic). “I would read 800 spec scripts per year and if they even got to your desk, it meant they were pretty good, but we’re looking for great spec scripts. It had to have an ingenious plot line, it had to be funny from page one, and had to be funny to the end. I would read them to the end and if it was 45 pages but ran out of steam at page 40, I would think, ‘This person is not a closer and they shouldn’t have started this script with a good ending.’”

He concluded, “I was looking for perfection and that person’s agent would often say there are other offers because a good script jumps out at you. It needs to be jokes, not just funny words. Young screenwriters should know your script is competing with 100 other scripts. The producer reading is not looking for a nugget of greatness, they’re looking for a reason to throw this script away and move on.”

“It’s Darwinian, so make it great off the bat. Make sure it’s great work before you bother people. Hard work is recognized, and laziness is not. You should bother people, if you have a cousin who knows someone in show business because you can’t be shy, but send them something great and just don’t bother me…”

This interview has been condensed. Listen to the full audio version here.