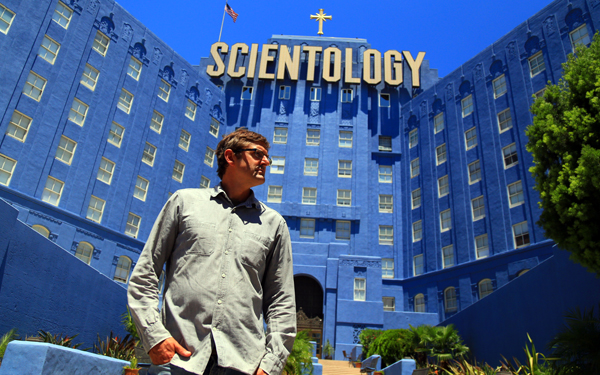

This spring, Creative Screenwriting is expanding its horizons to explore documentary films. As usual, our emphasis will remain firmly on the writing process. And what better place to begin than with Louis Theroux, an award-winning documentary maker whose latest film, My Scientology Movie, is in US cinemas now.

Louis Theroux is perhaps best known for his Weird Weekends series, in which he explores various American subcultures, often taking an ostensibly light-hearted approach. However, his more recent films have tended to explore more serious subjects, such as criminal gangs in Lagos, Neo-Nazis in America, paedophilia, meth addiction and alcoholism.

In all his films, Theroux takes a non-confrontational approach, concentrating on the stories and lives of the individuals whom spends time with. At times frustrating for the viewer, who might wish him to probe more directly into the issues, the result is a series of remarkably intimate portraits of members of society towards whom we might not usually expect to feel any empathy.

His most recent film, My Scientology Movie, focuses on the Church of Scientology in the US. Unable to make contact with individuals who are still in the church, Theroux concentrates on former church official Mark Rathbun, whilst producing a number of dramatic reconstructions of incidents that Rathbun witnessed.

This leads both Theroux and Rathbun into increasing conflict with members of the Church of Scientology, who resort to ever-more bizarre tactics to impede the making of the documentary, including filming the filmmakers.

Creative Screenwriting spoke with Louis Theroux about the attraction of the weird and the dark, shaping the story, and finding the right questions.

Will Pugh filming Louis Theroux in My Scientology Movie, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

How did you get started in the business, and what made you want to be a documentary maker?

My first job in television was working for Michael Moore – in 1994 he hired me as an on-air correspondent on his NBC show TV Nation. I had never thought seriously about getting into documentaries prior to that.

Before that I’d been a print journalist on a local paper in San Jose, California, and then at Spy Magazine. I’d thought a little bit about working in television but more as a writer of sit-coms, never as someone on screen.

Michael hired me because some friends who were then working for him as writers had recommended me. It was his idea to put me in front of the camera. I think he liked the idea that I was inexperienced. Basically I was a slightly awkward, gangly British guy with glasses, and I think he realized it would be funny to send me out to meet American extremists.

Michael Moore in Bowling for Columbine © 2002 – MGM

Since your early Weird Weekends series, it has almost become a cliché for critics to point out that your subject matter has become progressively darker. But it seems to me that there was a dark strand running through your earlier work as well. What draws you to these subjects?

Thanks for noticing that. There was almost always a little undercurrent of seriousness, even in the early days of Weird Weekends, with the possible exception of one or two episodes, like the UFOs one or the Infomercials ones.

I’ve always been fascinated by the weirdness and darkness of the human condition. The ways in which we sabotage ourselves. In some ways I think I find it reassuring that we are almost all of us grappling with the same unacknowledged craziness.

At first glance, My Scientology Movie seems an unusual film for you – your approach is usually to get to know individuals personally, whilst this film focuses on a group who are not even available for interview. But as the film progresses, it seems that your subject is not the Scientology movement, but Marty Rathbun. Was this always your intention?

Someone commented that they thought it was more My Marty Movie than My Scientology Movie. The intention was always to examine both sides of the story: to accept that the ex-Scientologists are also fallible, and that they have their own version of events.

I’m also drawn to paradoxes and apparent contradictions. I was on a journey with the ex-Scientologists and Marty in particular. He’s a fascinating man; very complex. I liked that he resisted seeing everything in Scientology as bad. He was still attracted to aspects of the tech and the military discipline. He’s got a whole spiel he does about non-binary thinking.

Marty Rathbun and Louis Theroux in My Scientology Movie, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Critics have described the film as being funny, and by the end the scientologists and their tactics seemed almost risible. Was this your intention?

Scientology is quite funny. A religion founded by a Science Fiction writer who had a habit of making up words and embellishing his CV. Religion has a silly side to it, especially when you look at it logically.

In general, when you look at Scientology material – the videos and books – they take themselves so seriously. It’s always over the top and epic. Some of the promotional videos released in the mid 2000s have the quality of infomercials. It’s the aesthetic of QVC applied to the timeless mysteries of the human spirit, which isn’t a natural fit.

You show the process of casting, scripting and filming scenes about Scientology. Did you ever intend to present these scenes as a finished product?

Early on in the development process we discussed making an actual film within a film – that we would maybe screen in Hollywood or release on the internet. But it came to seem a bit arch and artificial.

Then we – myself and the director John Dower – realized the re-enactments should just nestle inside the documentary, and that they would function both as illustrations of what Scientologists think and do, and also an excavation of Marty’s thinking. And also, I suppose as a way of looking at the Hollywood process itself.

Louis Theroux and actors in a reconstruction from My Scientology Movie, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

You seem interested in turning the camera on itself, and including yourself as a subject. What are your thoughts on the effect of the observer on the observed, and the extent to which this should be avoided or embraced?

I do think the non-interventionist school of documentary making can be a little overrated. You are there as a filmmaker, interfering, questioning, producing, so why not embrace that fact?

Many of favourite documentaries – and indeed works of literary non-fiction – are about immersive first-person journeys. As a participant in scenes you can shake things up, you can provoke and question. Especially in a story like this one, it was about making myself a lightning rod for the attention of the Scientologists, since so much of what makes them interesting is how they react to perceived criticism from “suppressives”. Like me.

Presumably you hoped to provoke the kind of response you got from the Scientologists, or at least were expecting it. To what extent do you approach a project with a narrative already in mind, and does this ever change during the filmmaking process?

Well, the hope was always that they would come back at us. That’s their MO. That’s what they’re known for. But I wasn’t sure whether they would do it.

The first time I noticed an unidentified camera crew filming us from across the street, it was a huge relief. The thing is, they can’t help themselves. It’s in the “tech” – the tenets and teachings of Scientology – that you have to strike back at suppressives. Having said that, they reserved their worst behaviour for the ex-Scientologists. Marty Rathbun bore the brunt of it.

Louis Theroux being filmed by Scientologists in My Scientology Movie, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

In a documentary you are ostensibly just presenting facts. But clearly you are also telling a story, through your script, your choice of footage, and how it is presented. So how do you go about writing your script, and to what extent do you think in traditional storytelling terms, such as the 3-act structure?

I do try to think in terms of three acts. It’s another way in which it helps to have me as a presence in the film.

We have some control over how I engage with the material – there is a kind arc to my involvement in the story. It’s not too formulaic, but I am always thinking – both in the movie and also in my television work – about the shape of the story.

In the Weird Weekends, there was a generally moment of participation, which would be somewhat climactic. But there was also sometimes a moment of attempting to challenge or even “rescue” (in a very mild sense) one of the contributors. A huge amount of the work of shaping my television documentaries is moving blocks of scenes around. The actual scripting of my voiceover is subsidiary to that, and generally just tries to support the actuality.

Louis Theroux and ‘Sarge’ in Louis Theroux’s Weird Weekends,”Wrestling”

One problem writers often face these days is not a lack of research material, but too much, so that it is easy to become lost in it, and be unable to find the story. Do you have any advice for screenwriters on how to approach and to use research?

I think it’s a common problem – I’ve faced it in my print journalism and my documentaries. In my television work it’s generally easier. We choose a handful of characters and let them to the work of telling the story – taking us through scenes, illustrating process.

My Scientology Movie was harder because we were having to generate the momentum of the story – by helping to stage these re-enactments. It’s easy to get lost in Scientology research, there’s so much there. But in general you have to identify the core idea.

In fact, there’s almost always a more basic, more obvious question that you’ve forgotten to explore, because you’re so deep inside the story. In My Scientology Movie it was basically, “Who are they? What do they believe?”

Then the deeper questions were: “What is the yardstick for abusive behavior?” “When does religious commitment become something more sinister?” “How much protection should we afford religion – and are there such things as good and bad religious faiths?”

Many years ago I read a book called Humanism and Terror by the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty. It was about Stalinism, and his basic point seemed to be that it would be hard to take issue with Stalinism and the show trials if they really had led to a genuine socialist utopia.

Many years ago I read a book called Humanism and Terror by the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty. It was about Stalinism, and his basic point seemed to be that it would be hard to take issue with Stalinism and the show trials if they really had led to a genuine socialist utopia.

Or to put it in the context of Scientology: If you truly believed that the planet’s only hope was through the mass application of pure unadulterated Scientology, and that without that we would be charred ruins drifting through space, what would you not be willing to do to make that happen?

Do you have any other advice, either for documentary makers or for screenwriters?

Work with good people. In general you’re only as good as your collaborators. On My Scientology Movie I had a terrific director John Dower. We had a brilliant editor, Paul Carlin. Simon Chinn, the producer, is obviously a docs legend. And I would also include Marty Rathbun, because it was only through his commitment to the filmmaking process that the concept of the re-enactments – which could have been gimmicky – actually became something deeper and more interest.

I’d also say: choose stories that you think are interesting, rather than because they feel socially important. Not that they’re necessarily mutually exclusive. But it’s a lot to ask of someone, that they give you an hour or 90 minutes of their time. The first duty is not to be boring.

[addtoany]