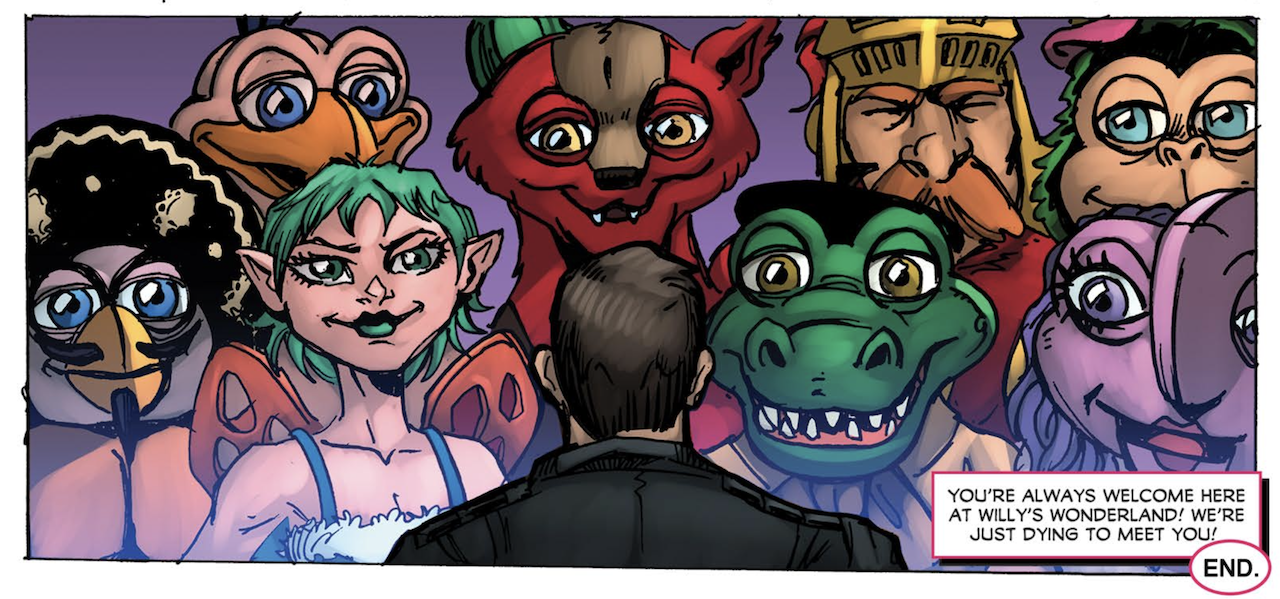

In 2021, screenwriter G.O. Parsons’ movie Willy’s Wonderland about a Janitor battling a team of evil animatronic animals in an abandoned theme park was released. Rather than work on a film sequel to his cult hit starring Nicolas Cage, Parsons turned his attention to comic books to expand the Willy universe.

“I hadn’t really thought about the idea of a sequel until after the movie came out,” ponders the screenwriter. Following a vocal audience request, Parsons explored avenues to creating more Willy’s Wonderland. Naturally, he considered Willy’s Wonderland 2 – the movie, but also television adaptations before settling on comic books.

“There was an idea of having a TV series where the Janitor (Nicolas Cage) would go and battle different evil creatures, but in a different setting. He would take a job as a babysitter and fight an evil doll. He would get a job as a gravedigger and fight zombies….” Parsons elaborates.

Eventually a comic book company called American Mythology reached out to G.O. Parsons and the producers to licensing the Wonderland world. They were really interested in exploring the origins of the serial killers prior to the events at Willy’s Wonderland. G.O. Parsons responded to this suggestion and pursued the comic book angle.

Without any background in the comic book space, American Mythology guided Parsons through the process of creating a Willy’s comic. Much like transitioning from screenwriting to novel writing, comic book storytelling has its own rules which G.O. quickly had to learn.

G.O. Parsons

The first Willy’s Wonderland comic was released a few months after the film.

From Screenplay to Comic

“The key elements of the comic were a serialized story component, tracking back serial killers, and an origin story; basically what happened in the theme park up until when the Janitor arrived,” says Parsons. “This is probably ten years prior to the Janitor’s arrival. We see kids playing on the machines and we see the animatronics being happy and kind. But then they’ll do something dark in the next page and kill a customer or whatever.”

“And when that happens, we go back in time even further, and we see the murdering animatronic in their human form and what crime they committed. They’re eventually institutionalized, and we see how all eight serial killers meet each other and decide to work at Willy’s Wonderland.”

Parsons collaborated with artists Puis Calzada and J.C. Spence. “They took what was written on the page in screenplay format and brought it to life using their own imagination. In a lot of ways, the artists are like the film director.”

Crash Course In Comic Book Storytelling

“The first thing I did was read scripts from comics American Mythology had done in the past. We’ve all read comic books, but we don’t see the script that actually produces the comic,” states Parsons.

Then there are the spacial constraints that are more rigid than film and television writing. Comics typically contain three to six panels per page. “You can’t go really over that so you have to use your dialogue very sparingly.” There isn’t space for monologues or deeper dives into the characters. “You really have to get to the point of the conversation because there just isn’t room on the page to have all the words.”

The rules of ultra-economic screenwriting apply to comic and screenplay writers alike. If the dialogue doesn’t fit inside a speech bubble, it isn’t added at all. The “lettering artists” complete the dialogue, so there isn’t time to redo it in a rewrite. In many respects, producing comics are a lot like animation where every frame is used without waste. “You can do a million takes in regular film, but you can’t do it in comics.”

Comic book scripts are more of a format than text documents. “It’s very sparse and to the point. It would start at page one, panel one – for example, in Willy’s Wonderland, Willy and his gang of eight animatronics are on stage singing and then you’d put Willy as far as the dialogue goes and he would say, ‘It’s your birthday and we want you to have fun.’ That’s it. That’s all you’d have for panel one. Then it’s up to the artist to create it.”

Comic books typically run at sixteen – thirty-two pages long. Willy’s Wonderland ran at twenty pages, leaving room for extras, bonus content and advertisements for the company’s other comic books at the end.

The film version of Willy’s Wonderland created a solid world and characters that Parsons stuck close to while writing his comics. The art work was influenced by a variety of comic books to create a distinctive look. “I remember writing in one panel, ‘Think of this panel from the Watchmen, just so that the artist could get the idea of the scope that we wanted to go with. And I knew that it was a beloved comic book that everybody would know,” says Parsons.

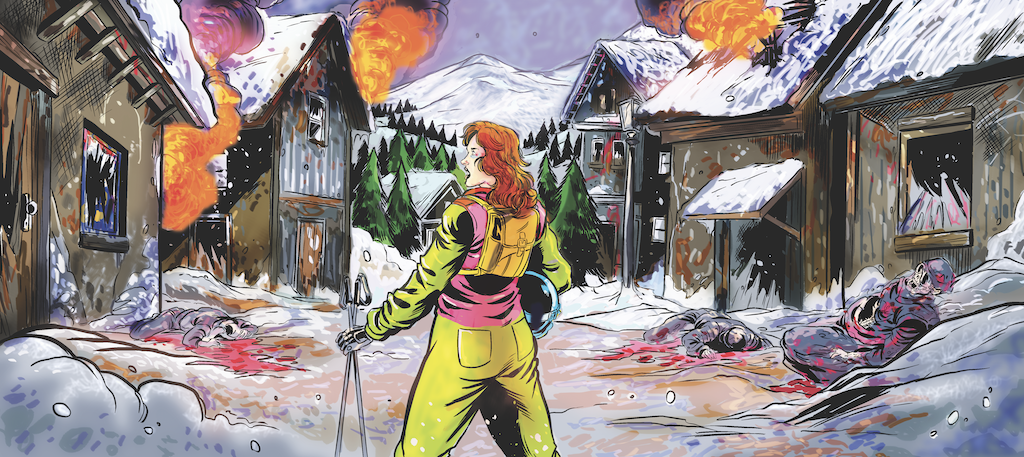

Beast Of Bower Boulevard, Parsons’ next comic book series was more removed from Willy’s Wonderland, so its storylines represent more of a departure from the original story. “It’s a completely open world where I could do whatever I wanted.” The Janitor isn’t a part of this series. Beast is set in a small ski town.

Parsons creates his worlds in a similar fashion to the way Stephen King creates his. “The Tommyknockers exists in the same world as The Stand. So that’s what I tried to do with Beast. It all takes place in the Eastern Sierras in Nevada, where Wonderland was set in Central Nevada. So it’s still in the same world. Wonderland exists in the world of the Beast of Bower Boulevard, but they aren’t specifically connected.”

By virtue of severe space limitations, comic book writers must express story, character, tone, and pacing quickly and efficiently.

“You can talk about character through dialogue which is also done in movies. You can also use captions within the frame to show what the character thinking or how they’re feeling – like we use in voiceover for movies. So, you can cheat it a little bit there and give the audience a little bit more about the character through captions.”

The main character in Willy’s Wonderland is a mysterious Janitor with very little backstory. His needs are immediate. He cleans and tries to the destroy the animatronics. The main character in Beast Of Bower Boulevard is a police officer in a ski town. His fiancée is an ex-convict and the daughter doesn’t really like him that much, so there’s that dynamic set up between the three. Beast plays more as a family drama as the family grapples with each other’s objectives and conflicts while they’re battling the dinosaur robot to stay alive. “It’s done mostly through dialogue and through those captions being able to tell what they’re feeling inside.” Writers need to select one or two key emotional drivers to make their point.

Beast Of Bower Boulevard

J.C. Spence, the designer of Willy’s Wonderland, comics believes that reading comics is a short-lived experience. “You read it, you have your sugar rush, and it’s done. A movie has a lingering effect. You’re meant to talk about it afterwards.”

There is little room to depict literary nuances like subtext or deeper themes in comic books. That’s not to say they are absent from them. They are neatly tucked away so they can be explored in film and television adaptations in detail. Comics also have a smaller. more specific audiences which are more attracted to the imagery and fast-paced storytelling of the medium.

Graphic Novels Versus Comics

Graphic novels are considered an expanded version of comics with some of the rules of ultra-economical storytelling being relaxed. Willy and Beast were always designed as the shorter form comics because that’s the door American Mythology opened for them. Parsons posits that many graphic novels were once comics. They grew is size and organically became lengthier graphic novels. Others started as graphic novels due to the large content sources. The medium also expanded into other genres like romantic comedies rather than stick to the traditional horror, sci-fi, or fantasy space of many comics.

Whether it’s a matter of economics or artistry, comics and graphic novels provide an additional avenue for screenwriters to create and distribute their work. This may lead to adaptions to film or television. G.O. Parsons states that the Willy’s Wonderland comics gave him a chance to expand the story world and give it a second life. Beast Of Bower Boulevard can exist as a standalone story without any expectation of further adaptation.

“Beast of Bower Boulevard is a way for me to take something that I’ve written and be my own pirate ship. I create a physical comic book, a piece of IP that can be shopped around to different places. It’s not a script, it’s not a spec. It’s a physical specimen that exists in the world. It’s a piece of IP that can be turned into something greater.”

In conclusion, G.O. Parsons advises writers interested in breaking into the comic book landscape to attend various group meetings and events to gain insight into how the industry works. It’s not imperative that writers have a comprehensive understanding of a comic book script format with panels. “You can keep your script as simple as a short story and write eight to ten pages. Think of ways how it can be artistically interpreted.”

Then you might want to research artists that align with your story tastes. “There are so many artists out there. You can find them on Instagram, TikTok, and X. Meet up with that person and see if they want to kind of do a creator/artist combo.”

If you’re a team, you can create the entire comic or hire an artist to draw a few panels. “Don’t be shy about getting your work in front of everyone and anyone, whether it’s comic book companies, producers, or anybody that can help you out.”

Comics should not be seen as a fallback to not getting your film or television script produced. “If you’re a fisherman and you throw out the reel and the reel is not working then you throw out the net. If the net’s not working then you get the dynamite you throw that in the water. One is not necessarily better than the other.”

[More: G.O. Parsons Battles Demonic Animals In “Willy’s Wonderland”]