First helmed as a populist novel by Mario Puzo of the same name in 1969, The Godfather had no aspirations of becoming a cinematic classic. Puzo was a notorious drinker, gambler and smoker with a mountain of debts. His goal was to write a best-selling pulp novel that eased his financial burden. He succeeded. Paramount Studios subsequently purchased the rights to the best-selling novel and had considerable difficulty in finding a suitable director and cast to translate its success into a profitable film. Paradoxically, they had problems with many aspects of the film ranging from casting to its length. They had little faith in its viability until a select few believed in bringing the story of sparring crime families to the screen.

Francis Ford Coppola, who co-incidentally was also short on cash and heavily indebted to Warner Bros., needed a hit. Francis stepped up and shared his vision of Puzo’s gangster family drama with Paramount executives. The Godfather rolled out across America in March 1972 and cinematic history was made.

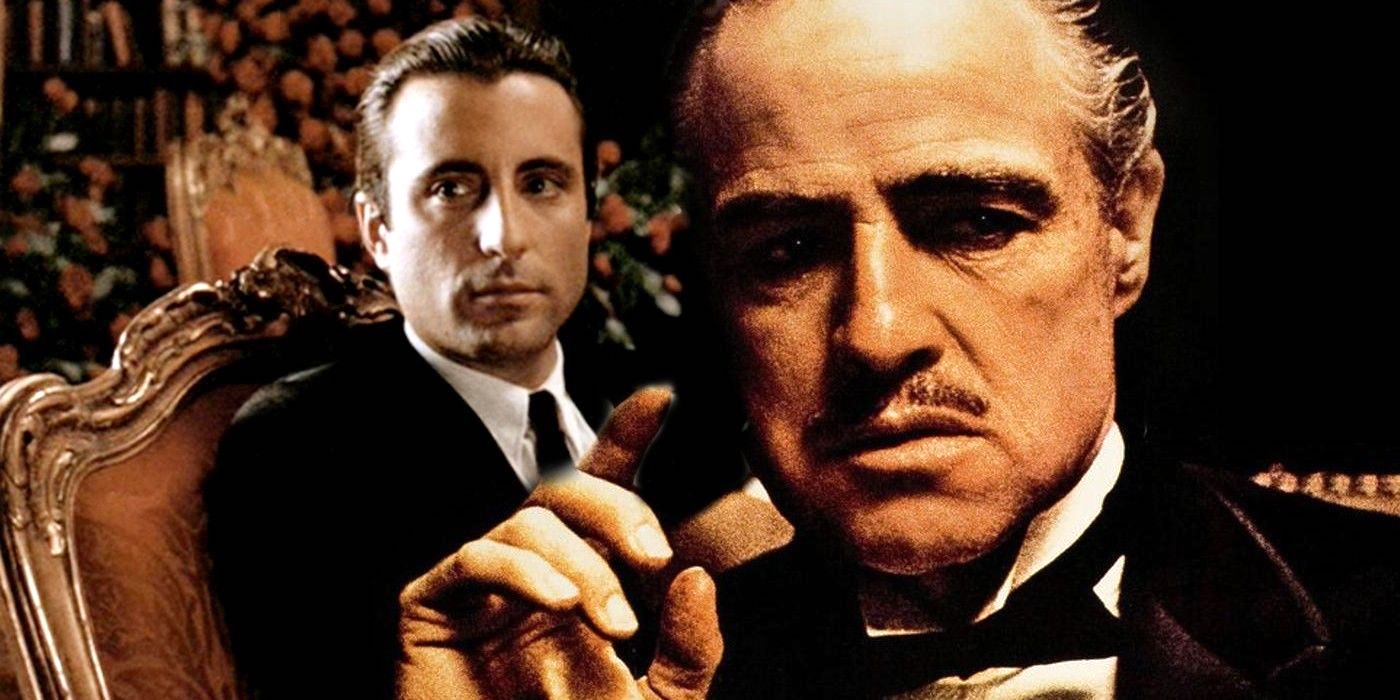

References to The Godfather are still prevalent in many film and TV shows, implicitly or explicitly, crime drama or comedy. There are emulators and parodies to honor the original. Film students are still instructed to make an enduring film that is as relevant today as it was back in the 1940s and 50s when The Godfather was set.

Fred Roos. Photo by Alexander Roos

Producer Fred Roos and archivist James Mockoski spoke to Creative Screenwriting Magazine on the fiftieth anniversary of this classic film and its lasting legacy.

The Making Of A Classic Film

“A classic film is one that people still want to see,” said Fred Roos. “It’s still written about, talked about, and not forgotten.” Zoetrope (Francis Ford Coppola’s company) archivist James Mockoski had a different take on defining the classic. “From Apocalypse Now to The Godfather, a classic film keeps finding a new audience while keeping the existing ones.”

Although The Godfather was restored and re-released this year, Francis continues to tweak and recut his films prior to doing so. He did the same with the re-release of Apocalypse Now.

Stories about organized crime and mafia families (particularly of Italian origin) continue to fascinate and entertain global audiences. Typically, they are set in the aftermath of deep social and economic shocks when there is rampant civil unrest and economic uncertainty. Faith in traditional government structures has eroded and crime is a means of survival and exerting power and control. The Godfather is set after World War II.

“Many crime family stories are about people who have grievances with authorities about how they’re being treated,” said Roos. These families are marginalized from mainstream society, so crime is their way of demanding their place and respect in it. “There’s some kind of urge in all of us to root for that,” he continued.

Mockoski believes that Coppola didn’t specifically set out to make a gangster film when he was offered The Godfather, but somehow, he made the gangster story his own. “He [Coppola] found a story about a family and their sons in Puzo’s novel,” said Roos.

James Mockoski. Photo by Paul Grandsard

Gangster films weren’t new in Hollywood at the time. However, they weren’t made by Italian Americans and they flopped. This contributed to Paramount’s reticence to make it.

The Godfather might have suffered the same fate outside Coppola’s tutelage. “As some have said, ‘You can smell the garlic,‘” joked Roos. “The sizeable Italian-American cast had certain behavioral touches that Coppola didn’t need to direct. There was something they brought with them.” However, Francis could instill that “East coast Italian family feel” in the non Italian-American cast through his direction. Fred Roos was quick to point out that Francis Ford Coppola was not a product of a criminal family. “His father was a great musician [flutist].”

James Mockoski added that Coppola drew on his formative experiences growing up in New York. “Francis told stories about what affected him and his family. In the scene [in The Godfather] where Peter Clemenza (Richard Castellano) is teaching Michael Corleone (Al Pacino), he tells him that’s the way he was taught to make sausages. That’s personal. Coppola could impart these small moments into the film.” Similarly, the unforgettable line, “Leave the gun. Take the cannoli” was drawn from Coppola’s youth when his father would come home from work with white boxes containing sweets. Thematically, it reinforces the notion of separating business from family. On an aside, The Godfather has even inspired its own range of cookbooks.

Robert Evans, a Paramount studio executive, was reportedly as notoriously difficult as Francis Ford Coppola according to Roos. “As difficult as he was, Bob was fanatic advocate for the film. Francis was incredible in the room. Whenever he took meetings with executives, he would do whatever it took in a dramatic way to sell his vision.”

James Mockoski recalled a recent conversation with Coppola. “The studio didn’t like a particular scene with Corleone and Sollozzo (Ari Lettieri) and asked him to reshoot it. Coppola returned to the first thing he shot with because his vision of his film was so strong.”

Wedding scene in The Godfather

Mockoski also mentioned that Paramount wanted to cut parts of the wedding scene where Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) did a trick for the children and put something in his mouth before he had his heart attack. “Coppola insisted that he wanted to keep them so he sneaked away and shot them just before the crew broke for lunch. Paramount reasoned that the audience will figure out Don had died so it was unnecessary. It was such an important scene to lose. It’s an iconic scene.”

Peter Bart, a young agent and Vice President for Production at Paramount who was instrumental in circulating the early drafts of The Godfather to secure a director. “He went to all the big name directors and got rejected. Then they approached Francis. They felt his Italian background could bring something to it. They also felt he could produce an arthouse film on a budget,” said Roos. Coppola eventually raised the budget to $7 million which was significant in those days.

The book was written by Mario Puzo, but the screenplay was essentially written by Francis Ford Coppola. “They would often book a hotel room and write for hours and days on end,” said Fred. “Then they would go downstairs and gamble.”

The Godfather also violates an often-taught rule of screenwriting. It had too much dialogue. “The film was very talky with minimal action and violence,” said Roos. He believes that The Godfather could still be made today, but the dynamics would likely be different. “Dramas are still difficult to make in the studio system today because it’s considered box office poison. It would have to be made at a lower budget, independently, or through a streamer.”

James Mockoski commented on Francis Ford Coppola’s remarkable ability to assemble a team. “Sometimes everyone in a team wants to put their own fingerprint on it, but Coppola’s team shared the same vision. Fred and Francis put a team together that we still work with today.”

Fred Roos pushed for Dean Tavoularis to production design the movie. “Francis hired Gordon Willis as his DP after seeing his work despite their rocky relationship.”

As a veteran film producer, Fred Roos offers some words of wisdom to filmmakers, “Respect film history and get up to speed with what came before. Watch films of the past from all over the world. Steal from the best.”

James Mockoski echoes these sentiments. “You can’t be a well-rounded filmmaker and have a singular vision of one genre. You need to understand where it came from,” he said. “Francis thoroughly researches film history before preparing for a new film. What other filmmakers have addressed your issue and how did they do it? This provides inspiration. Ideas don’t naturally come to you in isolation.“