“There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.” ―

The Los Angeles County Department Of Children & Family Services manages the largest foster care system in the country. The sheer numbers of children in the foster care system combined with the audience’s hunger for reality compelled Oscar-winning filmmakers, Deborah Oppenheimer and Mark Jonathan Harris, to produce an HBO documentary on the topic. They shared their views with Creative Screenwriting Magazine.

“I did volunteer work at a local public school and met a six-year-old boy who was very positive, happy and a leader in his class,” said Oppenheimer. When she spoke with his teacher, she discovered that he was living in an orphanage in Los Angeles. This sparked her interest in the foster care system. “I didn’t realize that orphanages still existed. I was inspired by his attitude and resolved to work with him.”

Deborah Oppenheimer. Photo by Mitchell Haaseth

Mark’s interest in the foster care system stems from his longtime focus on issues of social justice as they relate to children. “I wrote five young adult books which dealt with traumatic events that were caused by their parents,” he said. Harris references his film Into The Arms Of Strangers: Stories Of The Kindertransport (2000) which examined children in war losing both family and home. Foster is a natural extension. “Children are wrenched from their families through no fault of their own.”

In conceptualizing Foster, Oppenheimer and Harris wanted to explore the foster care system in Los Angeles over a long period of time. Los Angeles has the largest child welfare system in the country which poses its unique set of challenges. Given that the documentary filmmakers are both based in Los Angeles, they got to work on their home turf. The scale of foster care activity allowed them to maximize their creative choices. Examining the foster care system in one city did not limit a wider audience appeal.

“The stories we picked [for the documentary] are universal and could have happened anywhere,” adds Harris.

Choosing A Documentary Style

Not all documentaries share the same perspective and narrative style. “We wanted Foster to be an observational film as much as possible,” asserted Harris. “We wanted to immerse you in the world of the foster care system.”

Their creative decisions were strategic in terms of the stories they wanted to tell and the documentary format. It wasn’t a matter of simply grabbing a camera and filming as much footage as the could.

“We spent a few years doing research to understand the foster care system and to decide on the stories we wanted to tell with the main characters. Casting is essential. It took us a long time to find the right central characters. Much of the connection between the characters and their stories developed in the editing process to weave these five stories together,” continued Mark.

Despite some of the narrative unfolding during the filming and editing process, Deborah and Mark did write an initial treatment to form the foundation of Foster, and also to secure funding from investors. “Once you find the characters, their lives are unpredictable. Their stories unfold in a way we couldn’t imagine,” adds Harris.

Mark Jonathan Harris

Harris elaborates on the main differences between writing a regular feature film and a documentary. “In narrative form, films you have complete control over the beginning, middle, and end. In documentary films, you imagine a narrative arc that you may not have total control over. You have to keep writing the film as you’re making it because reality is often so different and hopefully more interesting.”

Developing The Project

The filmmakers spent several years researching their documentary. This represented the longest part of the pre-production process. The filming, which was done in continuous real-time, also took a few years. The post-production was also time-consuming. The final stages of storytelling are often found in the editing bay.

The stages were not always clearly defined. “We had to follow the story. There were story holes we needed to address so we had to film additional segments. We had to come to a satisfying ending that indicated the direction in which the story was going. We knew Foster only represented a slice of their lives,” said Mark.

Deborah added that they didn’t start filming until they raised their finance. Foster isn’t the type of documentary that could be filmed in stages. So much of it relied on case studies, court cases, and other procedural elements.

Choosing The Subjects

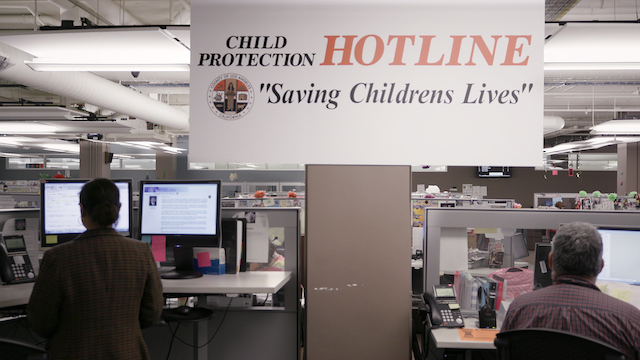

Once they decided on a five-story interweaving format, the filmmaking duo began recruiting subjects to track. “We knew we wanted to show the earliest point at which a child can enter the system. This includes a newborn baby with drugs in their system. We liaised with the Children And Family Services Hotline who referred potential subjects such as first time young couples struggling with their first baby,” recalls Deborah.

Harris and Oppenheimer were in a fortunate place enabling them to attend the first court hearing which is mandated to occur within 72 hours of birth. Oppenheimer and Harris navigated the child protection system with insights from social workers, lawyer, and other advocates, the film offers a realistic, yet hopeful perspective on a community that needs society’s support.

Courtesy of HBO

Apart from monitoring newborns, Oppenheimer chose to explore children “aging out of the foster care system and the challenges it brings such as education, economic, employment, nutrition, and housing.” These issues are exacerbated by typical adolescent behaviors which lead such teenagers into the Juvenile Justice system. Despite the seemingly insurmountable legal roadblocks, a character in the film wanted to show they “could go from zero to hero.”

Mark and Deborah also felt a responsibility to show an example of a foster parent grappling with the system.

A non-profit organization also brought another character, Jessica to their attention. The idea of a teen mother who experienced the entire system was attractive to them because she wanted to rebuild a dysfunctional foster system from within.

There is more to selecting subjects than their camera readiness. “First you have to gain their trust so you can tell their stories in a way that is meaningful and beneficial to other people,” mused Harris. “Their stories should also be therapeutic to them. The audience is a sympathetic witness to what they’re going through. We did not want to be damaging. It’s sometimes difficult to draw the line between realism and exploitation.”

Foster isn’t all sour and gloomy faces. The filmmakers relished the chance to create both tender and laugh-out-loud moments, especially in some court scenes. It releases tension and creates a sense of authenticity and hope.

Courtesy of HBO

What The Documentary Filmmakers Learned

One of the shocks of the foster care system for Harris and Oppenheimer was the staggering complexity of the system.

They also realized the long-lasting impact of trauma on foster children as well as their resilience. “We tend to write off foster kids. There are so many negative stereotypes about social workers, the judges, and a broken system. On the contrary, we found that people were very dedicated despite their stretched resources,” said Harris

Oppenheimer was also struck “by the lack of underpinning in some of these kids’ lives. They have challenges that most people in life will never face. They need somewhere to turn and people they can depend on.”

Documentaries often serve to inform, educate and create awareness in the general public. We also wanted to generate “greater compassion, greater willingness to view this population as individuals and, understand the potential of foster kids,” stated Deborah.

They also wanted to spur community engagement. The community can take on many forms. Adults don’t necessarily need to take in a child if they can’t sustain the required care. They can also mentor, help with resume-building life skills or lend a sympathetic ear.

“The problems of foster care aren’t simply the result of poor parenting. They’re the result of larger social issues such as poverty, lack of education and opportunity, and racism. Foster care was always meant to be a temporary fix for families in crisis. We need to do more to assist struggling families and take a more preventative approach to intervene before there’s a crisis rather than act as a triage,” declared Mark.

Commercial Potential Of Documentary Films

Documentary films are often restricted to the film festival circuit or poorly-funded television channels.

Despite their smaller budgets and marketing, documentaries can flourish financially. The pair acknowledge that it’s a great time for documentaries to find an audience. “There are so many TV and streaming platforms to watch them. People have an appetite for reality amidst the flood of action films cramming our cinema screens,” said Harris.

Fortunately, this represents a viable economic model to make documentaries. Their sale prices have risen dramatically. “So long as people have a hunger for reality to see the truth. Documentaries provide access to worlds that audiences don’t otherwise have access to,” adds Harris.

“The craft of documentary filmmaking has become more sophisticated and employs all kinds of narrative techniques to keep the audience engaged. This film speaks to educators, legislators, families, and anyone who has any contact with the foster care system regardless of age, gender, or class.”

In terms of wisdom for emerging documentary filmmakers, Mark proclaims, “persistence, passion, commitment, and patience” is key. “This is what keeps you going when you develop a project over four years.“