This interview contains spoilers.

It all began with a seven-page book by Henry Selick & Clay McLeod Chapman about two mischievous demon brothers named Wendall (voiced by Keegan-Michael Key in the movie) and Wild (voiced by Jordan Peele) who escaped from the underworld to make it big in the overworld with the help of rebellious outcast hellmaiden Kat Elliott (Lyric Ross).

Many years later Peele (Get Out, Nope) and Selick (Coraline, James And The Giant Peach) harnessed the magic of animation to bring Wendell & Wild to the screen. Henry Selick shared his thoughts on the process with Creative Screenwriting Magazine.

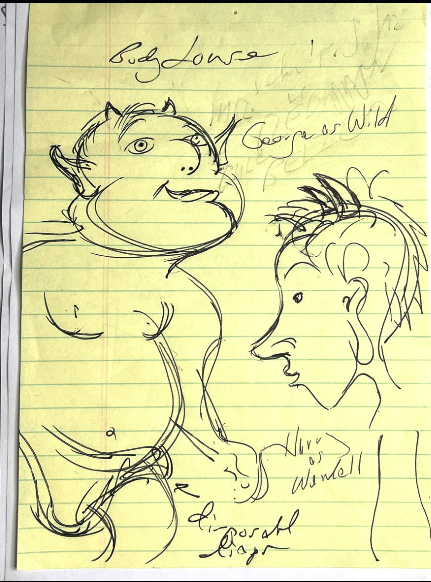

Sketches of the Demon Brothers by Henry Selick

“My main source of inspiration began twenty years ago when my sons were small,” said Selick. They were aged two and six when they were typically defiant and ebullient. Henry drew a sketch of them as demon brothers to creatively deflect his frayed patience. Based on these sketches, he changed his sons’ names and co-wrote a short story titled Wendell & Wild. “I actually went to school with a guy called Wendell Wild,” he quipped. “Buffalo Belzer (played by Ving Rhames) was then known as The Redneck Of Darkness, Manberg the janitor (played by Igal Naor was then called Mandrake.” It was a personal project between Henry and his sons and never intended to leave the house.

Many years later, a sketch comedy TV show called Key & Peele starring Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele caught Selick’s attention. After three seasons, he was so inspired by their comedy that he reached out to them so they could help him bring Wendell & Wild to fruition. “I wanted to bring their sense of comedy, play, and improvisation to it,” said Selick. It was 2015 when Peele finally got back to Selick because he was also a huge fan of stop motion animation. “Jordan had actually taken a puppetry class in college,” added Selick. Peele pushed to be a full collaborator on his project so he wrote a script that greatly impressed Selick.

Jordan Peele checked in at various points during the development and production process to offer his input. “He would raise red flags about issues that didn’t really matter to the film,” continued Selick.

This twin spark set the wheels in motion to expand the story into a feature film. Henry wrote the first draft of Wendell & Wild. “Jordan was the global thinker and the tone master. He helped with the movie story.” Then Selick’s manager Ellen Goldsmith-Vein, who co-produced the film. suggested they concurrently publish a Wendell & Wild book. Selick conscripted another writer for the book, but that project fell flat. He plans to revisit the book in the future.

Selick’s arcane knowledge of animation allowed him to balance the story with the visuals. Directing came naturally to him through decades in the business. One of his key concerns was balancing comedy with horror so that the movie retained its core PG audience.

Selick and Peele set out to make a children’s PG-13-rated film. They tested the movie across various age groups to ensure that it didn’t become too dark and scary for the intended audience. “The ten to fourteen year-olds loved the film the most. They understood it, the best. As the audience got older, they become more confused by it.” The tweens were probably the most receptive age group.

Selick doesn’t believe there’s anything in Wendell & Wild that’s too scary for childen.”There’s nothing in there that will damage them. It’s strong medicine emotionally and visually, but we don’t want to scar kids with excess.” Some scenes in Coraline were much darker.

One Film – Two Screenplays

Henry Selick wrote two versions of Wendell & Wild. One version was for the people who work most closely with him. “I go pretty deep and sketched out the scenes in exhaustive detail so they get a strong sense of the world I’m imagining.” The actors, animators, costumers etc. also provided feedback to fine-tune the story and the look of the film. The second version is the regularly formatted one for the studios. “The public consumption screenplay trimmed things down to convey the essence of the story. I added more detail here and there to illustrate a scene.”

Henry added that he doesn’t work all that well under pressure. When he goes away on his own, his best ideas often come to him.

Dramatically, Wendell & Wild is told as a dual protagonist narrative – the Demon Brothers work as one dramatic unit while Kat Elliot is the other. “The A-story is Kat and the B-story is close behind with the demons.”

Wendell (Keegan-Michael Key) & Wild (Jordan Peele) Photo courtesy of Netflix

Selick doesn’t claim to forge new thematic territories in his stories. Rather, he takes old themes and makes them his own. Since Kat is the main character in Wendell & Wild, her story is the most prominent – notably the issue of losing her parents and put in foster care where she was brutally bullied. “We made her loss harder and deeper because she feels totally responsible for her parents’ death.” The issue of loss soon grew into a central question of how child carries the impossible burden of guilt. “How does it shape them and affect how they deal with the rest of the world when they’re trapped in the past?” Kat eventually wades out of this emotional quicksand, accepts that it was an accident to finds comfort in the present.

Kat has been judged by her rebellious punk rock identity all her life. She challenges perception, assumptions and conclusions that others draw about her. “Don’t judge too quickly.”

I don’t do friends – Kat Elliot

The filmmakers presented her backstory which initially came later, right up front. “This makes it easier for the audience to give them a more direct path to follow.” After Kat summons the Demon Brothers to the world of the living, she believes that they’ll bring her parents back and everything will be fine.

After her parents are temporarily resurrected following the selfish deal she made with Wendell & Wild to bring them into the Land of the Living so they could build their amusement park, she becomes more selfless and choses saving the town from private prison developers in favor of letting her parents go forever. “She learns to live in the moment.”

Sister Helley (Angela Bassett) takes the mantle to rid Kat of her Hellmaiden powers that allowed her to summon the Demon Brothers. She tells Kat, “The future isn’t set in stone.” Kat musters all her courage to confront the Shadow Monster and own her demons and not be controlled by it. She becomes the mistress of her own fate.

Henry Selick. Photo by Paul McEvoy/ Netflix

The Demon Brothers Wendell & Wild often follow the comic dynamic of Laurel & Hardy or Abbott & Costello. Wendell is the rule maker and Wild is the rule breaker. They bounce off each other.

The filmmakers also took great care to develop the villains. “We set the story up to assume that Buffalo Belzer is a giant demon. He’s harsh and derives great joy from frightening his prisoners, the Souls Of The Danged.”

The janitor is also somewhat villainous. “He’s selfish, but when push comes to shove, he’ll give up his collection of demons to get his friends back.”

Wendell & Wild dabbles in some socially-conscious issues, namely how for-profit corporations run private prisons for greed rather than reform. Once again, Selick wrote these scenes based on his wife’s career while Peele finessed the tone. Selick’s wife became an advocate for at-risk kids, of which Kat is one. “Certain kids mess up one time and get kicked out of school. They don’t get counselling or help they need. They get pushed out into group homes where they only learn to survive not thrive.” Selick became acutely aware of the fragile line between kids learning at school and being pushed into a pathway – first juvenile justice system, then prison. This is most likely Kat path. This cemented Selick’s decision to make humans the villains in the story, not the monsters and demons.

The filmmaker worked with color-coded index cards to track of the many storylines in his story. “It’s the most effective way to determine what stays in the film and what’s extraneous. I draw key scenes on these cards and also do beat boards. The feelings that we get from these images will earn a story beat and make it into the final film.” These beats can also reduce a plot point to one short scene which is essential when creating animation. “The beat boards and key scenes go hand in hand.”

Henry Selick balances the light with the dark in many of his movies. “One movie I always go back to is The Night Of The Hunter (1955) with Robert Mitchum.” It guides his style.