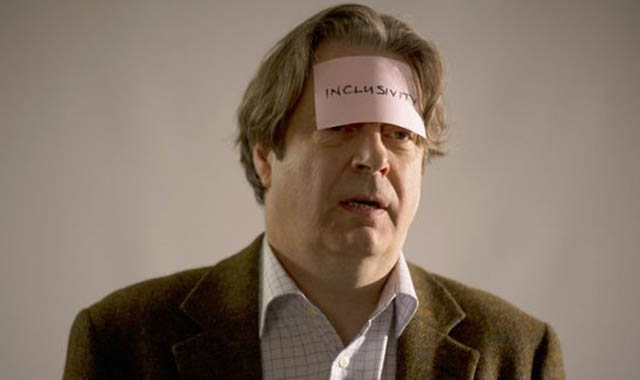

Armando Iannucci is a film and TV writer and broadcaster, who has written, directed, and produced numerous critically acclaimed television and radio comedy shows during his screenwriting career. His screenplay for the film In The Loop was nominated for an Oscar and his iconic series for BBC, The Thick of It, won 5 BAFTA Awards. His HBO comedy Veep also picked up numerous awards. His film adaptation of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield will be released in January 2020 (UK) and has just been nominated for 11 BIFA awards, including Best British Independent Film and Best Screenplay. He is currently in the midst of post-production on his new HBO series Avenue 5.

Armando shared his thoughts on building and sustaining a successful screenwriting career with Creative Screenwriting Magazine.

Why did you choose political satire as your preferred brand of comedy?

I didn’t really choose it and I don’t see it as a ‘brand’… and actually, I don’t really like the phrase ‘political satire’ at all. (Ha. We just got smacked down)

All I’m interested in doing is making stuff that’s funny. I suppose you write about stuff that interests you and I’ve always been interested in politics because I want politics to work. Therefore, when I see politics failing or political arguments that are specious and illogical, I’m naturally drawn towards examining why they’re like that. I suppose a lot of my comedy is to do with how people use rhetoric to mean something different from what the words they’re using actually mean.

Armando Iannucci

How do you road test a joke so that it lands in its funniest form?

I don’t think you should write for an imaginary audience. I tell screenwriters who are starting off, write what makes you laugh, not what you think makes a television executive laugh. Otherwise, you won’t write your best stuff and you have to, in the end, trust your own judgment. Having said that, sometimes you shoot stuff or write stuff and you have no idea whether it is going to be funny because it just depends on the circumstances and where it lands in the story – what the atmosphere is like in that scene, what other characters are there.

I tend to deliberately over-record stuff, knowing full well that some of what we’ve written won’t make it, but also feeling quite excited about the idea that some of the stuff that we thought might be a bit mad will actually work really well in the final edit.

The road-testing is really just a case of seeing what survives the editing process. And then I always make sure that there’s another pair of eyes and ears watching the cuts as we get near to the final lock, because you can get so close to material and so over-familiar with it that you can occasionally forget whether something is funny because you’ve watched it a hundred times in the edit.

When you’ve got what you think is a cut that tells the complete story – but it might be a little over-length – it’s always good to play it to an audience, because then, just from hearing the laughter (or absence of laughter), you get a sense of what seems to work and what could do with reining in.

How do you decide whether a certain type of comedy is worthy of development or not?

Again, it’s the personal thing – what amuses you? What makes you angry or irritated? What’s the one thing that’s getting you most worked up? When we were developing Veep, the thing that I was drawn towards was the complete sense of logjam and inactivity within Washington – the fact that nothing was getting done because the US Constitution is predicated on the assumption that different parties will work together to come up with a compromise. But that doesn’t work if both parties say they won’t talk to each other.

That was the starting point there. Right now, I think what’s intriguing me is the idea that the Zuckerbergs of this world, who think that they’re fundamentally decent, nice people, then expand from that assumption to ‘therefore we must be allowed to do anything we like, including not paying any taxes’. That intrigues me.

Can you go too far in political satire?

I have a sort of general rule which is, when you’re looking at a subject – especially if it’s a sensitive subject – work out what your boundaries are and then, on at least one occasion, cross them, just to see what happens. I’m not really in favor of ‘you can say anything you like, and you can offend anybody you like’ because I think you end up writing lazy stuff.

It’s quite good to have some kind of constraint, even if it’s self-imposed, just to give you a sense of something to fight against, something to push up against. But that said, I don’t think there’s any subject that’s off-limits in terms of comedy. The Death of Stalin, for example, was full of labor camps and mass killings and we didn’t make light of that.

The Death Of Stalin

But I also felt that the only way you could tackle how a state machine could come to the conclusion that that sort of behavior was in everybody’s best interests was through comedy. And interestingly, part of our research threw up the fact that under Stalin, people circulated joke books about Stalin – jokes about Stalin – which, if you were overheard saying, would get you shot. And yet people still felt the need to make fun of that regime, almost like saying ‘they can put you in prison, they can take away your livelihood, but as long as you can still make a joke about them then they haven’t got your mind.’

How do you balance truthfulness with fictionalization in satire?

Well, we’re in a strange situation today because jokes are lies, aren’t they, really? They’re distortions of the truth. They take something that we all perceive to be fact and then stretch it – to absurdity, to breaking point. But actually, that’s what politicians are doing now. They say the most outrageous things and then, if there’s an outcry, they try to get away with it by saying ‘but, couldn’t you tell that was a joke?’ To which the response is, well if it was a joke, it was a terrible one.

It’s interesting that the comedians who’ve been able to grapple more effectively with the likes of Donald Trump and those politicians who talk about ‘fake news’ are the ones who act like journalists – like John Oliver, who has a team of researchers and forensically examines political arguments and analyzes any illogic within them.

It’s almost like there’s been a job swap: politicians have become the providers of their own entertainment and therefore comedians have in turn become journalists. But we’re also in a strange situation in that if you make a joke that in any way offends, some comedians feel that you can’t do that. Or comedians who do then come under a lot of criticism.

I don’t think you should offend for offence’s sake, but you do have to ask the question, what’s wrong with being offended? If you have a set of beliefs, shouldn’t they be strong enough to withstand a joke? And if they’re not strong enough to withstand a joke, how firmly do you hold those beliefs?

How has your writing voice evolved during your career?

I think you always learn from each project that you do. I suppose – and I think this is true for lots of comedy writers – you start off writing short-form comedy like sketches and therefore you go for the gag, or the one-liner, or the funny monologue or a very self-contained absurd situation. And then, as you get older, I don’t know whether it’s relationships and having children and family responsibility, but you kind of go away from that rat-a-tat-tat aim into something that’s more long-form – into narrative.

I really enjoyed the switch from doing short-form gags to actually being interested in people and in characters. Often I’m finding in an edit that I’m taking funny lines out because they slightly spoil the comedy in that scene if they feel too well-written. If they feel that the character, in that situation, would not come up with that kind of a line under the pressure that they’re in, it destroys the credibility of the moment. I remove the funny line and somehow the scene becomes funnier as a result. But it’s always a learning process, I don’t think you ever reach a point where you think that you know everything. That would be dreadful.

Do you have a preferred format for artistic expression – TV, film, radio?

No. It just depends on what it is you want to say and what kind of comedy you want. I really love writing columns, essays, and journalistic pieces as well. Sometimes you’ll have an idea that feels like something you want to explore in great depth, and that would suggest maybe a TV show where there’s multi-episodes. Whereas others, you want to come up with a whole world that’s self-contained from start to finish and that instantly makes you think it’s a movie. But I started in radio so I’m always interested in that too. Maybe it’s to do with language or sound? What people say is always important.

What is your writing process from the germ of an idea to a finished product?

A lot of displacement activity. The hardest thing in the world is to sit in a room on your own and write. Whereas I find it very easy to gather groups of people together and make each other laugh – and actually you then end up, or the group collectively ends up, coming up with ideas not necessarily that no one of us would have come up with, but which would have taken far longer to come up with on your own. I love the spark in collaborative writing. But then there is also the slog, the slog of making sure, once you’re with a script, that every line is as good and as strong as it can be. That’s the hard work. The draft, after draft, after draft, after draft, after draft.

The Personal History Of David Copperfield

What advice do you have for emerging satirists?

That makes it sound like it’s a job where you wake up and you go ‘who should I satirize today?’ So my first piece of advice is, don’t ever think like that. (our second smackdown) My writing advice is always to go for what makes you laugh as opposed to what you think makes other people laugh, and keep writing – because you learn so much from anything you write. You learn by your mistakes. There’s now no excuse. You don’t have to wait for the phone call – you can write a blog, you can invent a character, you can go out and film something. And even if it’s only seen by three people, you will still have learned something from that, so that with the next thing you do, you can apply whatever it is you’ve learned.

The Personal History of David Copperfield is a departure from your typical work. Why did you write this screenplay?

I don’t think it is a departure really – in that, The Death of Stalin was one historical drama and this is another set in a separate historical period (1840). The imagination and inventiveness of Dickens’ language, characters, and situations struck me as being extremely contemporary. Re-reading the novel, it actually felt like it had been written as if for today’s audience.

Looking at some of the ideas – the big stage of the country as a whole, the state of the nation – there are so many things about poverty and homelessness and rich and poor existing side-by-side. There’s social anxiety, status anxiety, David trying to work out whether he fits in among his friends and his work companions. It all felt very, very contemporary. So what I wanted to do was make something that, if you turned the volume down, might look like it was in the past, but once you turned the volume up and watched them and listened to them, you’d think, no, this could be happening now.