By Ramona Zacharias.

Graham Moore

Barely on the cusp of his mid-30s, screenwriter Graham Moore has achieved phenomenal heights with his first screenplay, The Imitation Game. In an early emergence, it topped 2011’s Black List for the best unproduced Hollywood script. The end product was 2014’s beautifully moving film directed by Morten Tyldum (Headhunters) and starring an ensemble cast that included Benedict Cumberbatch, Keira Knightley, Matthew Goode, Allen Leech and Mark Strong. It’s a film that has garnered a slew of industry accolades, including 5 Golden Globe nominations, 6 Critics’ Choice nominations and 8 nominations at the upcoming 87th Academy Awards – all of which included nods for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Based on Andrew Hodges’ 1983 biography Alan Turing: The Enigma, Moore’s screenplay tells the story of Alan Turing (Cumberbatch), a British mathematician and cryptanalyst who helped crack the Nazis’ Enigma code during the Second World War. A collaborative effort at Bletchley Park, the work of Turing and his colleagues was held classified for some 50 years. As a result, Turing was never recognized for his heroic efforts during his lifetime, but was in fact criminally prosecuted for his homosexuality and chemically castrated.

I spoke with Moore to talk about the film, the success that has surprised him, and about bringing to the big screen a story that has been on his mind since he was a teenager.

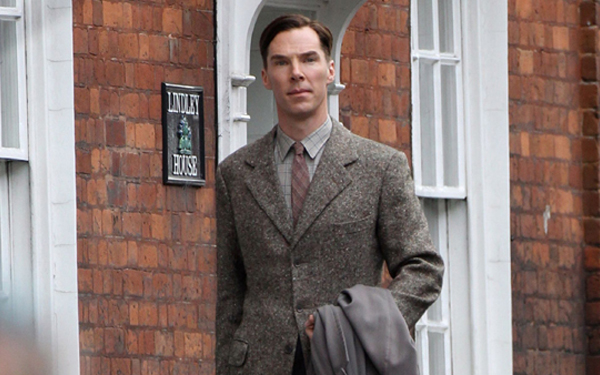

Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing in The Imitation Game

The first time I watched The Imitation Game I chided myself for my history knowledge not being what it should! But I’ve learned that Turing’s story was not very well known until this past year, at least in many circles. What initially sparked your interest? It’s evident from the film that this was a passion project for you.

I’m glad you can tell that! It certainly was. I think it was a passion project for me and for all of us on the team.

I was lucky enough, I feel, to have been exposed to Alan Turing’s story very young. When I was a teenager growing up in Chicago, I was this tremendous computer nerd. I went to space camp, I went to computer programming camp…and among kind awkward, tech-minded teenagers without a lot of friends, Turing was almost this campfire legend. It was sort of this secret history of World War II, a secret history of computer science. Sort of like: “Did you know that the guy who actually invented the computer and broke the Nazi Enigma code was gay and was punished by the government for that fact after the war?” It was an amazing true story and always this source of wonderful inspiration – this guy who never fit in in his own time, but precisely because of that saw the world in a way that no one else had and was able to accomplish things and think up ideas that no one else had before.

So I had always wanted to write about him. It seemed like if anyone’s story deserved proper feature film treatment, it was Alan Turing’s. His story had been told in a couple of books and a wonderful play, but there had never been a film. And it seemed like Turing’s legacy deserved one. Not that many people knew the story and his legacy deserved so many things, among them a film to put it back to the rightful place and center our understanding of World War II, where his legacy certainly belongs.

But if you go around Hollywood and you call people up and you pitch them this movie about a gay English mathematician in the 1940s who commits suicide at the end…those aren’t exactly the buzz words everyone’s hoping to hear! So it was a very hard go – but it’s one of the reasons I’m so proud of our producing team and all us who came together to fight for years to get this movie made.

The Enigma, by Andrew Hodges

Tell me about working with Andrew Hodges’ biography of Turing and creating your screenplay. Did you work closely with him as well? What other resources did you utilize?

My very smart producers had optioned Andrew Hodge’s 1983 biography of Alan Turing. And Hodge’s biography of Turing is kind of the first and most important Turing biography. That’s the book that’s really the reason anyone knows Turing’s name at all. And Andrew is responsible for the declassification of a lot of the material surrounding Turing and surrounding Bletchley Park. His work is on Turing is really second to none. I got to work with Andrew and talked to him a lot during the writing of it. He is an amazing resource.

But his book also came out in 1983, so there has obviously been a lot of material declassified, or dug up, since then. So there have been a couple of other really good biographies that I was able to use as well, and then a lot of more primary source stuff – Turing’s own letters, his writings. In the 1990s there was a bit of a campaign in the UK to get people who had been at Bletchley Park to talk about their experiences. The law was changed in the 90s in the UK so it was legal for them to do so. And this is one of the most amazing things about the story – they kept the secret for 50 years. No one talked about it. There are these stories of people being married for 50 years and not telling their husbands, not telling their wives, what they’d done at Bletchley. It’s remarkable. So starting in the 90s, you’ve got people beginning to talk about it a bit, and going on interviews. We got to watch some of the videos, going through written accounts of people’s memories.

I think one of the trickiest things for all of us was that there is no audio recording of Alan Turing. There is no video recording of Alan Turing. All we have are written accounts; the memories of people who knew him, and his own writings. So from my perspective, in putting together his dialogue and putting together his mannerisms, and then from Benedict’s perspective as an actor, doing the same sort of work…it was really an interesting process of collaboration. We couldn’t just do an imitation (so to speak!) of someone – because there was nothing to imitate. You had to sort of put together from the ground up and really think through “what would he have been like?” You’ll notice Benedict uses this sort of slight stutter sometimes – this kind of odd manner of speech, and a slightly high voice. We spent a lot of time experimenting with that because we had no recording. So really trying to look at different accounts of how he spoke – one would say “he had this really thick stutter and could barely get a sentence out” and another source would say, “it wasn’t that bad, he just had a little bit of one from time to time” – and just doing our best.

So much of working on The Imitation Game was a process like that – of having everyone involved, doing as much research as we possibly could, and then meeting up in London in a rehearsal room and hashing it all out. And saying: “Oh, you have a source that says that? I have a source that says this…which do we think is more accurate? What do we think makes more sense? What do we think really happened?”

I think for all of us, one of the most wonderful moments – maybe the most meaningful moment since finishing the film – was when we did a private screening for a dozen or so members of Turing’s family. One of his nieces was 18 when he passed away, so she has pretty good memories of him from her childhood. She came up afterwards and said that watching the film felt like watching her uncle alive again, onscreen. I know for Benedict and myself and Morten and the whole team, it was like “OK. We got it. We feel like we did this right.”

Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing in The Imitation Game

What motivated you in telling Turing’s story?

I think my goal with this piece, and the goal of everyone on our team, was to do right by the legacy of Alan Turing. I think that Turing had been so mistreated by history in his own time, and then even after his death, that the goal of this film was to present historical corrective to that and to give him the credit that he never got in his own life. And to pay tribute to him and what he’d done, and to do so accurately and responsibly.

There is a tremendous responsibility when you’re telling a true story like this to tell it right, accurately, and to convey the essence of a person. The goal was always “can we open up Alan’s mind to an audience?” We always talked about this as being a subjective film – the story you’re hearing is from Alan’s perspective. It’s Alan’s voiceover that narrates the piece. Every scene is shot from Alan’s perspective. The camera never rises above Alan’s eye level – that’s one of Morten’s little notes, because it’s all shot from Alan’s point of view. And in the writing as well, we always wanted to tell Alan’s story – because his is the story that so deserved to be told, and hadn’t properly been told before.

Tell me a bit about how you write and what your process is like.

I guess my process is different for different things. I write novels as well, so I go back and forth between books and screenplays. Which I find helpful, because whenever I’m doing one, I end up wishing to God that I could do the other one. The way I think about the difference is the volume level between the two. If I’m working on a film, there’s so much noise, there’s so much volume. There are conference calls and emails and meetings and all this stuff…and if I go write a book, it’s just me, alone in a dark room for months on end, years on end, just typing. I like being able to go back and forth between the experiences.

The things I’ve been writing for the past few years have all been historical pieces, or even if it’s modern-day, it’s still based on a real event and still very research-heavy. So part of the process, before I even start writing, is months and months of research. The research process is, in some sense, the most fun for me – just getting to learn about a subject that I didn’t know very much about. With Alan Turing, I knew a lot about him to begin with…but once you sort of begin to peel the onion, you run into so much more. And then I’ve also been able to work on things where I knew nothing at all going in. I wanted to work on them because it was like “I don’t know anything about that…it sounds like a lot of fun.”

So much of my process ends up being about lots of research and then finding ways to dramatize that research – how we take the raw data of historical events and turn that into drama, whether that’s on the screen or on the page.

As a history buff, what was the experience of filming in Bletchley Park and other areas Turing lived and worked in like?

It was important to everyone on the team that we shoot in England, around London, and use as many real locations as possible. Especially because we were such an international production in some ways – I’m American, our producers are American, and our director is Norwegian. But it’s such an English story, it was really important to use an all-British cast, all-British crew, shoot in London, and really get the essence of the very British story at the heart of it.

And of course what we wanted to do was, whenever possible, shoot on the real locations. So we spent a week at Bletchley shooting there. All the scenes at Sherborne, the boys’ school Turing attended and where he falls in love with Christopher Morcom, are all shot there, in the real location where those scenes would have happened.

We used real props whenever possible. So every Enigma machine you see in the film is a real Enigma machine, used by the Nazis during the war. You can’t see on screen the very scared-looking man from the insurance company, just off-frame, making sure we didn’t break the thing. We made this movie for $15 million and so breaking an Enigma machine was not remotely in our budget!

But yeah, I think it was great with the actors getting to touch the real things and the real devices. We were sitting there in Bletchley Park, in the real beer hut…and I think it was Allen Leech who turned and said “I bet if we walked around here and dusted for fingerprints, we could find Alan Turing’s fingerprints somewhere in this building right now”. And we all kind of gasped, thinking “I’m sure he’s right”. And it reminded everyone every day of the responsibility that we had as filmmakers to get this right – because Turing and everyone at Bletchley deserved a film that got it right. We felt proud to have that daily reminder of the task at hand and its importance.

Bletchley Park

Let’s talk about the cast and what they brought to your characters. Did you have certain actors in mind when you wrote the screenplay? How involved were you in the casting process?

I never write with specific actors in mind. I feel like you never know who you’re going to get and I don’t want to let it muddy up my thoughts in one way or another. Of course writing something like this, you think about Benedict Cumberbatch. Before I’d even written a word, we’d talked about him – I’d been a huge fan of his work for years. But I never thought we’d get him! It was one of those beautiful moments, for me and for everyone, when once we started casting, he raised his hand right away and said, “When are you doing this, how can I be a part of it – I’ll clear my schedule, just tell me when you’re shooting and I will be there. This is an important story and I have to be a part of it.” Keira Knightley did the same thing. Morten said at one point, he was so shocked by how quickly casting was going…”No one said no”. Even someone like Matthew Goode, who took a part that is probably smaller than a part he’d expect to play in a film of this size. But he did it because it just felt like an important story, a story that he wanted to be a part of telling. Same with Allen Leech.

I was involved in the casting, and I also got to be an executive producer on this – because it was a spec, I had a lot of control of the piece. I was involved in the casting, I was on set every day, I was in editing once a week. Morten is so inclusive about his process. That was important to all of us going in. And partially because we were such a small team, everyone needed to be involved, at all points, because there was so much work to do.

We made the film independently – it was completely independent financing, for $15 million. We had no big corporate infrastructure so there were no “bean counters” looking over our shoulder, if that makes sense. There was no board of directors looking over our numbers, saying “We know you want to cast so-and-so, but if you look at the foreign sales numbers we can get out of Russia, could you please cast this other person instead”. There was no one there doing that, where if we had been a studio, or even any sort of bigger company, that could have happened. And that’s why we were so lucky to just do it independently on our own so we could cast anyone that we wanted, we could make any creative decisions that we wanted, throughout the whole process.

The Black List 2011

Tell me about nabbing the #1 spot on the 2011 Black List. What changed for you after that?

That was a funny day! It was a great honor. I think the Black List does a lot of good in Hollywood, and I’m very honored to see people in Hollywood responding to my work that way.

It got a lot of attention for the script…and it came at a funny point, because we had just optioned the script to Warner Bros. when the Black List came out. So we sort of already sold it. Part of the history of this is that after the spec went out, it got a bit of attention to it and there were some very fancy names who were flirting with doing it – and because of that, Warner Bros. picked it up and so we spent our “lost year” trying to make it at the studio. Trying to make a movie about a gay English mathematician who commits suicide at a major studio went about as well as you would expect it would!

So we kind of lost a whole year as part of that process. But we had set it up so that Warner had a year to make the movie, and if they didn’t make the movie, we would get it back. So we got it back, and they were lovely about it – they were so gracious about giving it back and making things very simple for us legally.

In the interim, the Black List had come out. Benedict had read the script because of it, and a lot of the actors had heard of it because of that. It meant that everything just went faster. It gave it this notoriety and meant that people who wouldn’t have otherwise read it, read it. Morten read it because of the Black List. When we set up our independent financing and decided to start talking to directors, he raised his hand very quickly, because he had already read the script.

So that notoriety we got from it increased awareness of the project. That’s what I think the Black List does better than anything in the world. A movie like this, which is about some pretty difficult, pretty non-traditional subject matter still gets read by lots of people who would normally not be inclined to read such a piece. And that is invaluable to trying to put together a movie like this.

Beyond its entertainment value, this film has also brought education and awareness to a very old, very serious injustice. Are you still seeing the effects of that and what kind of reward has it been in its own right?

I think, for me, the most flattering and the most beautiful moments I’ve had over the course of finishing and promoting the film have been after screenings when people will sometimes come up to me and say: “Oh my god, I had no idea any of that happened”. Or “I had never heard of Alan Turing before…I can’t believe he really did all that and no one knew”.

I had this one guy come up to me after a screening and he put his hand on my shoulder and just said “I’m a computer scientist and I actually wrote my undergraduate thesis on Alan Turing – and I didn’t know he was gay. This movie was the first I heard of it.” He didn’t know that he had been persecuted or that any of that had happened. That for me was so profound, that this is a guy who, in some ways, his ideas are well known, but the man behind those ideas has been so hidden and locked up by history.

In moving forward, we really do hope that this film can bring attention to the other 49,000 gay men who were convicted and persecuted under the same barbaric statute that Turing was. We were very thrilled when we found out that Turing was pardoned, for his supposed crimes. But I also think there is something tremendously unfair in the idea that Turing was pardoned because he happened to be probably the greatest genius of his generation. But the other gay men who were convicted – they deserve no less justice, simply because they didn’t happen to be of a genius at the level of Turing’s. They also committed no crime. And sometimes even the word “pardon” seems problematic, because none of these men needed to be pardoned – they didn’t do anything wrong. It’s the government who needs to be pardoned – the government is the entity here that committed the real crime. And so we’re very proud that this film – in addition to being an entertaining film – can also be part of a broader conversation about “what can we do to right this injustice”.

The Real Alan Turing