By Brianne Hogan.

Steve Cuden

Steve Cuden’s love for movies is practically embedded in his D.N.A. “I have had film in my blood stream since I was a little boy,” he says. “I have been watching television and movies since I was a child. In fact, it used to be the bane of my father’s existence. I used to come home from school and watch The Three Stooges. He would ask me, ‘Why are you watching that?’ But I turned it into a career.”

His career has spanned Broadway and film and television, having written the globally successful musical, Jekyll & Hyde, as well as numerous screenplays and some 90 episodes of TV. Not surprisingly he is one of the leading authorities when it comes to screenwriting and currently teaches Cinema Arts students at the Conservatory of Performing Arts at Point Park University in Pittsburgh.

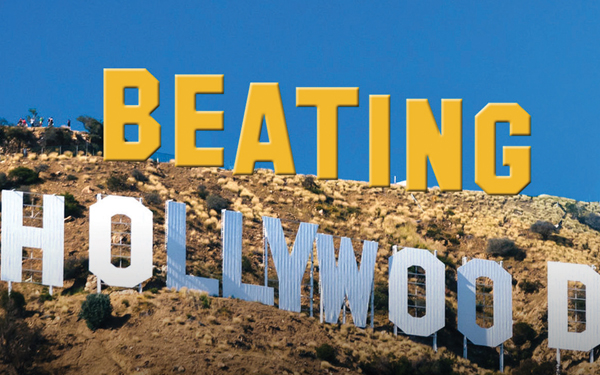

Now Cuden is spreading his wealth of knowledge with the release of his latest book, Beating Hollywood: Tips for Creating Unforgettable Screenplays, 40 Classic Movies Analyzed.

Creative Screenwriting chatted with Cuden about creating compelling characters, the essential beats that all successful Hollywood films have and where new writers often go wrong in terms of crafting their screenplays.

Henry and Lisa’s engagement party, from Jekyll & Hyde the musical

What was it about films that you connect with?

That’s a great question. I think movies affect people on a deep level. In our hearts, in our souls, and sometimes in our minds, but most of the times it is in our hearts and souls. Because what we sell in our scripts, we sell emotion. We don’t sell intellect, we sell emotion.

I have a pretty healthy sense of humor, so I love movies that make me laugh. And I love movies that touch me very deeply and tear me apart. There’s nothing that I like better than walking away from a movie and having a deep sense of catharsis.

Catharsis is one of the things that I teach because that is why we watch movies and TV shows, it is to achieve that emotional release. So that’s what I try to achieve in my writing, and that is what I try to teach to writers. Because when you get to that cathartic moment at the right moment in the story, when everything is resolved, I think you have not only a serious chance of selling that story but also connecting with audiences and making a lot of money.

What led you to write the book, Beating Hollywood?

I had had a concept quite a long time ago in my writing career. When I was unsure of how to form certain stories, I would go find two or three movies that were somewhere in the same ballpark that I was writing – in those days, they were in VHS format – and stop and start and break them down into narrative beats, and then figure out how those movies were structured. Over time, I used to think that this would be a very interesting thing for other writers to see.

What drove me to write the book is to show others – amateur, emerging writers, as well as professionals who might want to work at the structure of how movies work – and that is what compelled me to write the book.

In a nutshell – without giving away the entire book — what are the essential beats that all successful Hollywood films have?

Every story that I am aware of which has had great success and has continued to be unforgettable has the same seven beats, or seven plot points.

Plot points are where the story takes a major turn. Sometimes it goes in a very different direction or pushes the story in a dynamic way. The plot points aren’t something I invented – they have been around for a very long time. They are: the Normal World, the Inciting Incident, the Point of No Return, the Midpoint, the Low Point, the Climax, and the New Normal. And if you can figure out how you can pace your story around those plot points – there are no rules how they are delineated, although there is a certain way that is most familiar to people – if you can wrap your story around those plot points, then you have a pretty good chance of having a story that people will follow, understand, and like.

However, you also have to have unique, compelling characters in conflict with others unique, compelling characters. That is really the secret sauce right there. Of course, there is a lot more to it [laughs] but that is the underpinning. All great stories must travel that road. It works for comedies, it works for dramas, it works for epics, it works for sci-fi and horror. All stories of a memorable nature follow it.

You’ve also written for Broadway and wrote the book, Beating Broadway: How to Create Stories for Musicals That Get Standing Ovations. How does writing a book for stage differ from writing a screenplay? Are the beats the same?

Here is what’s great: musicals, which I know well, are a little different from plays. There are many plays that follow the seven plot points, and there are many that do not.

The big difference with the straight dramatic play is that it can talk about a topic and go vertical with it. You can start at the beginning of the play and continue talking about it endlessly, never leaving the topic.

Whereas movies must move horizontally, they must move forward. Otherwise people will not be compelled to sit there and watch it. So musicals, in particular, are very closely aligned, structurally, with movies. Musicals must move forward and not go vertical.

So, a good example of a vertical play would be Waiting for Godot. Really, those characters don’t change much. They talk about a lot of things, but the play doesn’t really move forward. But you will not find a successful musical with characters that do not move forward just like a movie does. And a musical shares the exact same seven plot points as movies do. Motion picture stories must move forward.

So, is it safe to assume you are an advocate of outlining and beating out the story before writing?

I am a very big proponent of outlining, and starting at the very beginning with the basic kernel of an idea, which would be a logline. Something that you could pitch to someone in 30 seconds.

Steven Spielberg has said that he knows he has a good story when he can hold it in the palm of his hand, which means it’s simple and he can tell it to you in one line and you get what the story is going to be.

You have to start with that kernel, then it will turn into a premise and depending on the length of the premise – most premises are two to five pages – and then you translate that into an outline. There are various types of outlines and treatments, but, basically you are figuring out what the characters are going through in the story. I prefer it in the beat outline, but I have written many treatments. Both work.

Some write beat outlines and then write the treatment. James Cameron famously writes a “scriptment” which is a combination of an outline and a treatment. So he will write a very long treatment that might be 60 pages long, and he will put scenes in it and bits of dialogue, so it is more fleshed out. So the more detailed the outline is, the more you have figured out the story moment by moment, the easier it is to transfer and transform that work into the actual script because you have worked your story out very well and you are filling in a lot of blanks and dialogue and so on.

My opinion is if you don’t go through that with a screenplay, unlike many novels that don’t have an outline at all, you have the tendency to go down blind alleys. A novel can be in the character’s head and talk about things and go off in random directions. Movies have to stay on a through line, and if you don’t, the audience won’t be able to figure out what is going on.

What I have learned about audiences, which I discuss in the book, is that they like complex characters and a simple plot. That is a great mantra to have when you are trying to figure out a story. I have seen students over complicate the plotting of their story. It is complicated for an audience to understand that, and, by the way, it is also complicated for the writer to write that.

I will use Spielberg’s movie, for example. What is Jaws? Jaws is ‘shark scares a town’. That is a simple plot – obviously there is complication in the plotting – but it is the complex characters that we care about and how they confront the monster. So I think in terms of how you construct your screenplay, doing it without an outline will most likely lead to failure and blind alleys from which you can’t get out. That is why people spend months and months in outlining things.

Roy Scheider as Martin Brody in Jaws

Where do many new writers often go wrong in terms of crafting their screenplays?

They go mostly wrong in two places. The first one being in terms of character development. Their main character doesn’t have a strong flaw that they don’t use in terms of solving the conflict in the end. The characters are flat. In Beating Hollywood, I refer to Lajos Egri’s The Art of Dramatic Writing, and how to develop a three-dimensional character.

And the second one — this is one I find in a lot of students’ work– that you have no conflict in a scene, in an act, in your story. Stories are about conflict. The main thing that audiences want – and they don’t even know what they want until they experience it – are compelling characters in conflict with other compelling characters. When they get that, they will be on the edge of their seat whether it is a courtroom scene or an action scene.

Conflict sometimes confuses people. They think it means guns and wars and people in a ring fighting each other. All conflict is: you have one character that has a goal — that is established in the inciting incident that will eventually resolve in the climax and lead to the catharsis – and that character will encounter one obstacle after another in achieving that goal. And in doing so the audience gets to see the story in a way that drives their passion to see it resolve somehow.

That’s why great stories are all about the development of suspense. Because how is that character going to get from here to there? An example of conflict can be: I am in a room and I can’t get out. It doesn’t require guns or battleships. It just requires a goal and something blocking the way. That goal can be quite simple, but especially powerful to the character.

What do you think is crucial in terms of character development and a character’s journey?

One of the things is the three dimensionality of the character: the physiology, the sociology and the psychology. Those are the three dimensions of the character.

What do they look like? Where do they come from? How do they think?

The next thing is we need to see some sort of flaw. Preferably as soon as we are introduced to them. Maybe it is physical like a withered arm or a skin disease. Or they have a flaw in the way they think. They have a great fear or phobia. We need to see that flaw established early on. That flaw is so important because it provides empathy for your protagonist. We need to like that character even if they are unlikeable.

Also, that flaw needs to be overcome or used in the third act in order to resolve the goal set by the inciting incident and if you can get there and reach catharsis in that third act and do all those things – it is a high bar to get over – you stand a real chance of having a hit on your hands.

Without three-dimensional characters with a flaw it is hard for the audience to latch on. The audience needs to like the characters or at least be empathetic of the character even if they are not particularly likeable.

An example would be McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. You wouldn’t necessarily want to hang out with him. There is something off-putting about him and yet we have empathy for him because there is something about him that we see in ourselves. Another example would be Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry movies. Not a great guy, not someone you want to hang out with, but you sure want to see him solve crimes. So, a compelling character you empathize with.

Jack Nicholson as R.P. McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

What are some of the most well-crafted movies you’ve watched and included in the book?

One of my favorite movies of all-time is Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Why is that a great movie to study? Because there you have two characters, the Yin-Yang of one another who complete each other, and it is male bonding love story without any romance. It has some of the finest action and dialogue ever written, so I think you can see how everything is short and smart and moves the story forward or gives us a better understanding of the characters. I think another one is Chinatown. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen it, but I always find something new about it. It is a very rich, well-written story.

You should also study the Godfathers – I and II. Because there you have the complexity of telling a story both in the present and past, which isn’t easy to pull off. I think most people stay away from Citizen Kane because of its complexity, but that is the best written movie ever made. You think that it is Kane’s movie, but it’s actually the reporter’s who is trying to figure out what happened to Kane. But we don’t spend much time with him, which is why it is really Kane’s movie. If you don’t study anything else, those movies will take you a very long way.

Orson Welles said he watched Stagecoach 30 or 40 times in preparation of Citizen Kane. How he got from Stagecoach to Citizen Kane, I have no idea, but there’s something to be said in watching all kinds of movies.

I am a big proponent of not limiting yourself. I think today’s writers need to be experts in lots of genres even if it isn’t your favorite genre. I say that because as more and more audiences become accustomed to old ways of how a story is told, writers need to find new ways of telling movies and stories. So that means cross-breeding genres.

There is only one way of knowing and understanding the genres and the conventions of genres and that is by watching lots of movies. You can become a great filmmaker and writers by simply immersing yourself in movies and TV shows, and reading scripts and books. I encourage people to read, read, read. We need people to think differently and that sometimes requires not just being a movie watcher.

Orson Welles as Charles Foster Kane in Citizen Kane

What’s the biggest piece of advice you can give to aspiring writers?

Writers must observe a lot of footage and write a lot of words. Brian Helgeland was talking about his career and I was stunned when I heard he wrote 60 films before he sold one. At that point, I had written 15 scripts and I thought I have barely scratched the surface and I know how hard I worked. And here is this guy who won an Oscar and it took him a long time.

The secret to writing success is Butt Applied Liberally to Chair. It means: writing, writing and writing again.

By the way, it is not about the writing really. It is about the rewriting. That is another secret I tell my students all the time. New writers have a very strong tendency to get through this very arduous task of completing a script and they are worn out from it. They say, “Okay, I am done.” I say to myself, “You are just getting warmed up.” It is not just writing. The art is in the rewriting.

And what is the biggest piece of advice you have received as a writer?

I would say two-fold. The only screenwriters who do not succeed are the ones who stop writing. So that was inspirational to me: keep going.

I think the other great piece of advice is to dig deep into your own soul when you are writing. The phrase that you hear often is, “Write what you know.” But the truth of the matter is I don’t think James Cameron ever met a Terminator before he wrote Terminator. So when that phrase is said, that doesn’t mean write your life. It means write what you know. Write what you are passionate about, write about what is in your heart, and that will get you very, very far.